One morning this past winter, Oregon Daily Emerald (ODE) publisher Ryan Frank ’99 took a group of Reporting I students—hailing from Kansas, Idaho, Nevada, Colorado, Oregon, and Singapore—on a tour of the Emerald offices. After telling them the number of Emerald newspaper racks around campus (120), Frank asked the group how many picked up the paper on a daily basis. A smattering raised their hands. Most said they got their news via Twitter or Facebook updates. If the Emerald had an app, they told Frank, they’d use it. One student pulled out his cell phone and explained how he uses an app that aggregates headlines from his chosen newspapers and sends him updates throughout the day.

Print newspapers have had a great two-century run, but today’s digital revolution has left them gasping in its wake, particularly among younger generations. A 2010 study by the Pew Research Center for People and the Press found that just 7 percent of people between the ages of eighteen and twenty-four read daily print newspapers. And advertisers know it. Increasingly, they are turning away from print and toward digital platforms that can better target the specific demographic they want to reach.

Newspaper circulation has been in a slow decline for two decades, but the recent decrease in advertising revenue has been “a precipitous fall off a cliff,” says Frank. According to the Pew Research Center’s Project for Excellence in Journalism, between 2000 and 2010 print advertising revenue in U.S. newspapers declined by half, from $48.7 billion to $23 billion; the sharpest decline has occurred since 2006.

For the Emerald—as for most newspapers—the conclusion is inescapable: change, or die. “Either change is going to happen to us,” Frank says, “or we’re going to drive the change.”

His preference is for the driver’s seat. Which is why he and Emerald staff members spent last fall and winter interviewing more than 100 Emerald alumni, journalism professors, and media professionals about possible strategies for the Emerald’s future. And it is why, at a mid-February meeting of the ODE board of directors, Frank laid out three options: to publish once, twice, or three times a week. Each option included beefing up the Emerald’s website to provide daily news and more integrated use of social media platforms.

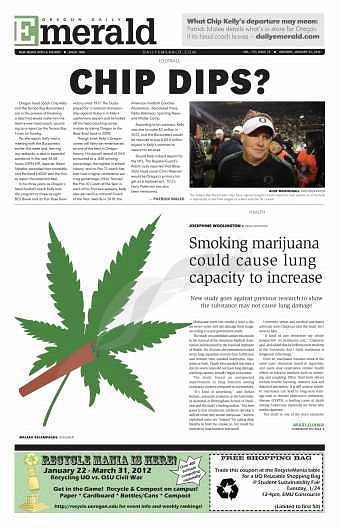

On May 1, the board made its unanimous decision. As of fall 2012, the Emerald will maintain a daily online presence, but it will publish a print newspaper just twice a week, on Mondays and Thursdays (the paper will come out daily the first week of every term). The twice-a-week papers will adopt a magazine format with increased emphasis on photographs, layout, and graphics. And the content will reflect the rhythm of students’ lives. Monday’s paper, Frank says, will feature in-depth, issue-driven stories and analyses of weekend sports events. Thursday’s paper will offer features, entertainment-related stories, personality profiles, a music calendar, and information about coming sports events.

Print isn’t dead for college students, Frank says. It just has to be in synch with their lives, interests, and time availability. And he believes that, if done right, a highly visual, twice-weekly product will fit the bill.

* * *

The transformation facing the Emerald is one of the most significant the paper has faced in its 100-plus years of operation. And Frank, many say, is just the guy to steer it through what will likely be rough waters, at least initially.

“He is coming at this with real passion and fire in his belly,” says ODE board president Melody Ward Leslie ’79. “He has the Emerald in his veins. He has ink in his veins. And now pixels have to be in all of our veins.”

A former Emerald sports editor, and editor-in-chief from 1998 to 1999, Frank spent the next eleven years at the Oregonian, where he covered city hall, real estate, and city business. He was brought on board at the Emerald in February 2011. In his new job as publisher, he dresses in blue jeans and button-down shirts. He sports a cinnamon-colored mustache and beard and has neatly trimmed hair the same hue. Thin and mild-mannered, he exudes the quiet intensity of a man who doesn’t intend to lose.

“I didn’t take the job to tend the paper,” he says. “I took it to make it the best college media company in the country.” This past January he posted a sign on the door to the Emerald offices reminding the staff of just that: “America’s Best College Media Company.”

But since Ryan took over as publisher, Ocker says, “everything’s better.”

The staff put out the best journalism the paper has done in years, he says, and the news staff came to trust in its like-minded mentor. “He understands what it’s like to be at the Emerald from a student perspective. You feel like you can go out and have a beer with him at night. It’s causal and comfortable. And he takes a lot of pride in what we’re doing.”

Editor in chief for 2011–12 Tyree Harris says Frank helped guide the news staff to professional-level coverage of a number of stories, including the firing of former UO president Richard Lariviere and the ensuing campus uproar that was covered by papers around the state.

“We were right in middle of it all. Up there with the major media,” Harris says. “And that was something that was not possible two years ago, given the structure that we had. We were live tweeting, live streaming. I haven’t seen that big of an effort around a story in my whole two years being here.”

* * *

In many respects, the ODE, like any entity that endures over time, has done nothing but change. Its origins date roughly back to 1891, when the campus publication Reflector first appeared. Over the next three decades the news organ changed its name, size, and publishing cycle. In 1920, reflecting the move to a weekday daily, the paper changed its name from the Oregon Emerald to the Oregon Daily Emerald. That change stood fast for ninety-two years.

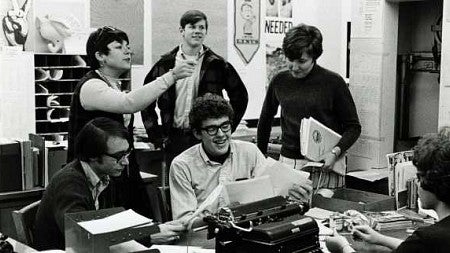

In the postwar years, the paper reverted to an inward, campus focus. But as the Vietnam War escalated in the mid-1960s, antiwar fervor boiled over on college campuses across the country. The UO, dubbed “Berkeley North” by some, became a hot spot of dissent. Campus buildings were firebombed. Student protesters battled with local police and held sit-ins at administrative offices.

The Emerald was in the thick of it.

“There was a lot of tension and stress between student editors and reporters and the University administration about what was going on—people protesting ROTC, wanting to have teach-ins, wanting the UO president to take a stand on antiwar activities, racial discrimination, poverty,” says Grattan Kerans ’73, ODE editor in chief from 1970 to 1971. The administration was being pressured from the business community and powerful alumni to crack down harder on student protesters. “It was tough times for everybody,” he says.

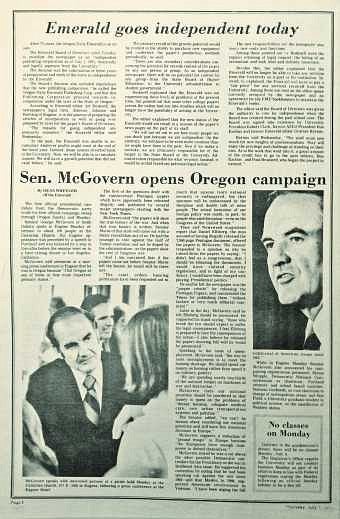

Concern over the ramifications of butting political heads with the UO administration and the state legislature had already prompted Paul Brainerd ’70, the ODE editor in chief who preceded Kerans, to begin looking into what it would take for the paper to become independent. (Brainerd went on to coin the term “desktop publishing” and cofound Aldus, the company that brought PageMaker to market.) At the Emerald, Kerans continued the process to attain independence. On June 29, 1971, he and UO president Robert Clark signed papers creating the ODE board of directors, which then established theOregon Daily Emerald Publishing Company, Inc.

“After seventy-three years, the ODE is on its own,” wrote the new editor in chief, Art Bushnell ’72, on July 1. Independence meant that the paper’s content could not be influenced by the administration or any other outside entities. It meant that it would stand on its own financial feet. It meant the paper would have to fight its own legal battles.

In the late 1970s, an Emerald reporter was sued for libel by a disgruntled local who had been featured in a story. The 2009 strike centered on concerns that the newsroom’s editorial autonomy wasn’t being respected.

Despite the rocky early years, independence turned out to be a financial boon to the paper. It enabled the Emerald to bank its end-of-year profits and use them to update equipment and make other necessary changes. In 1994, the ODE became a 501(c)(3) nonprofit corporation, which meant the paper no longer had to pay taxes on its profits.

The timing was fortuitous. Financially, the 1990s were a good decade for the newspaper, says business manager Kathy Carbone. National advertisers were placing ads in college newspapers because they were the best way to reach the demographic advertisers were after—college students. “We were making money without trying,” she says.

But the millennium ushered in change and challenge for the newspaper industry as a whole, and at the Emerald. National advertising dwindled, Craigslist pirated away classified ads, and the digital generation increasingly turned to the Internet for news. In 2008, the country was slammed with a severe recession. The ODE, which had already weathered some tough years, took a deeper hit in revenues and investments. In a 2009 report, prospective publisher and consultant Steve Smith—the hire that caused the two-day newsroom strike—reminded the ODE board that the Emerald “has been in the red eight of the last ten years.” The paper kept its head above water by tapping into reserve funds. But, warned Smith, “there is too little left in reserves to properly support the Emerald through two or three years of continuing red ink.”

Smith’s dire warnings did not materialize, in part thanks to careful budgeting. And athletics. In 2008, the UO hosted the U.S. Olympic Team Trials for track and field. The Emerald was the only print media to have a daily presence at the event, and the opportunity helped the paper end the year in the black. In 2010, the Duck football team’s 12–0 season and the run up to the 2011 Bowl Championship Series (BCS) championship game created statewide buzz and advertiser interest, resulting in another profitable year. During the team’s successful 2011 season, game-day issues, a special summer football magazine, and the buildup to the Rose Bowl helped keep it there. This summer the Olympic trials return to Hayward Field, promising another boon for the paper.

But in the long run, says Frank, that profitability is not sustainable with the paper’s current structure.

“The way we have become profitable is by managing and reducing expenses,” he says. The ODE professional staff of seven has been cut by half. One department, Creative Services, has been eliminated. The Emerald is debt-free, but to stay that way requires restructuring.

“You can’t take the existing infrastructure and ask people to do things completely differently,” he says. “You have to create new niches, a model that is different from the past.”

“That type of journalism is what’s getting lost today,” Frank says. “If there’s a way we can help support it by bringing ideas to professional newsrooms, then we all win in that process.”

Andy Rossback, next year’s editor in chief, is wasting no time instituting change. He is restructuring the newsroom into print and digital sections, and plans to hire a managing editor of digital. Digital-side reporters will cover breaking news, maintain the online paper, and contribute to the print editions, he says. On the print side, three seasoned reporters will follow specific, big-issue beats, which will allow them to write in-depth stories throughout the school year. Similarly, each of the paper’s three feature writers will cover distinct topic areas.

“We’re trying to think of things that aren’t the normal system, but will also add meaning to the content,” Rossback says. “We want to cover wider topics, and we also want to create a certain amount of compelling journalism.”

The Emerald is also instituting a start-up tech company, called the Garage, that uses technology and crowd-sourced data to build and sell specific services. The first product will be a mobile site that posts student evaluations of professors, Frank says. An app to share Ducks football stories and photos is in the works, along with online services to help students evaluate local dining and housing options. Future ideas include creating photo books, apps for student groups, and video services for various campus departments.

The business venture has two primary goals: to subsidize the Emerald’s public-interest journalism, and to provide students with relevant, real-world skills.

“Whatever field they enter,” Frank says, “students will have to know their way around every tech tool out there.”

Having the Emerald cease being a daily newspaper is a bitter pill to swallow for board members, alumni, and even some current staff members. But many back Frank’s efforts to keep the Emerald vibrant and self-sustaining—because the alternative is unthinkable. For almost a century, the ODE has created a home away from home for scores of staffers, prepared them for careers in the outside world, and given individual students the opportunity to see what they were made of. The transformed Emerald will continue that tradition, but will also be competitive on the digital field—providing online news coverage throughout the day, showcasing multimedia content, and giving students experience that will prepare them for the increasingly digital media market.

However radical the steps the Emerald has to take to survive, supporters say, it is imperative the Emerald take them.

“If we are not here in five to ten years,” says Ocker, the ODE’s former managing editor, “then we will all have done a great disservice to the students who come to the UO.”

—By Alice Tallmadge

Alice Tallmadge is a freelance writer and adjunct instructor in the UO School of Journalism and Communication.