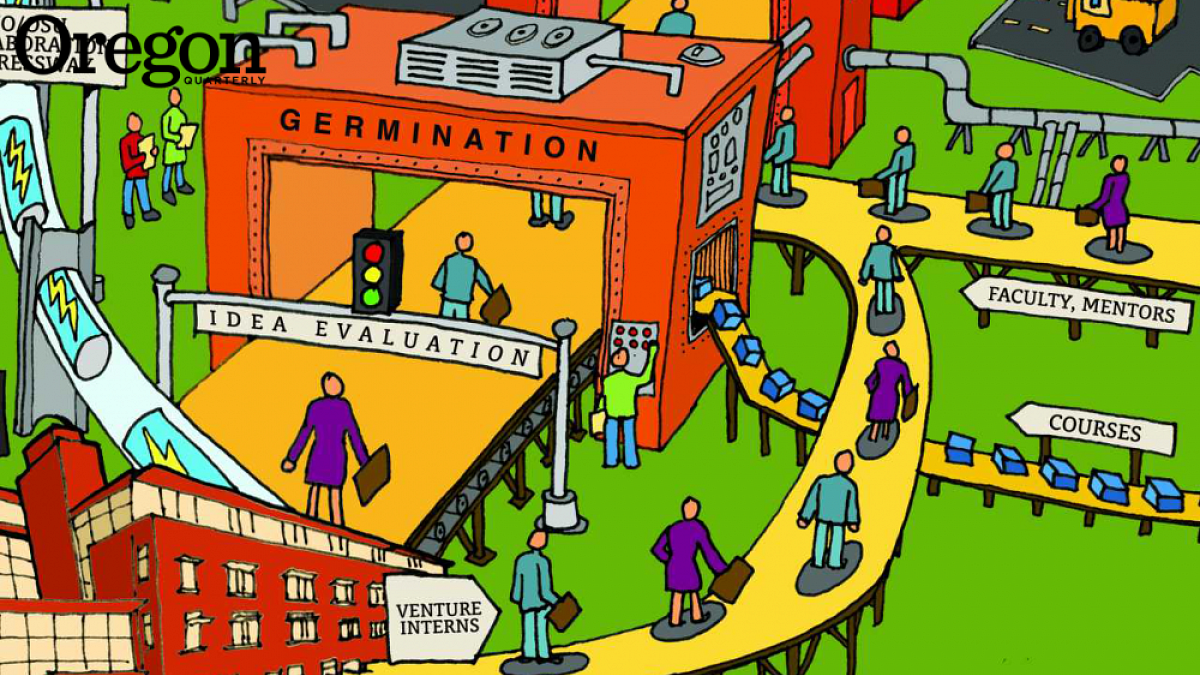

RAIN will create a regional center for innovation that brings together community and academic resources from the University of Oregon, Oregon State University, and the cities of Eugene-Springfield, Albany, and Corvallis. The program aims to make it easier for innovative entrepreneurs—primarily in the scientific research, high-tech manufacturing, and software-development sectors—to stay in the area, and to progress from having a great idea to finding the needed facilities, mentoring, and venture capital to turn that idea into a successful company.

"Ideas are only the first element of the process," says Kimberly Andrews Espy, the University of Oregon's vice president for research and innovation and dean of the graduate school. "It requires intention to support the idea until it gets to the point where someone wants to invest in it. We need to make it easy to get these services."

The network will have two components: physical spaces known as accelerators, and the innovation network. The accelerators (in Eugene and Corvallis) will include office space and well-equipped laboratories, providing important resources that are seldom available to emerging companies lacking the cash to invest in specialized equipment. Eugene companies will also have access to campus core research facilities, such as the UO's Center for Advanced Materials Characterization in Oregon (CAMCOR) and the Genomics and Cell Services Center; those in the Corvallis area can take advantage of OSU's Electron Microscopy and Imaging Facility and the Microproducts Breakthrough Institute.

RAIN's second component, the innovation network, will extend its helping hand beyond the incubators, providing budding companies across the region with business and legal advice, connections to entrepreneurs-in-residence, and access to potential investors.

"You can have great facilities and lots of scientific instruments," says Chuck Williams, assistant vice president for innovation and head of the UO's Innovation Partner Services, "but without the mixing of the right people from different disciplines, it's hard to get a business off the ground. How do you get those rings to connect into the knowledge bases you need to have?"

So bring on the RAIN. "It's a one-stop shop," Espy says, "an innovation ecosystem."

Out of the lab and into the world

The UO and OSU already have a terrific track record of sprouting startups from research that began on their campuses. In 2012 alone, the two universities collectively brought in nearly $400 million in research dollars, and between them, they have launched more than 45 spinoff companies and created about 600 jobs.

"One of our gems has always been tech transfer," Espy says, noting that the UO ranks among the top 20 universities in the country in terms of return on innovation (the rate at which research spending generates revenue). Much of this success has come through the College of Education, which has been outstanding in the development of assessment tools that have been widely adopted nationwide. "Now we need to expand our successful model to broader segments of research," she says.

"There is a greater sense now among faculty that there is satisfaction in the application of our technology to real-world problems," she adds, noting that attitudes have changed in the past few decades. Also, students are more interested in entrepreneurship than ever before. "Even undergrads are doing startups," she says. "If you want to make it big these days, you have to do it yourself."

RAIN is aimed at young companies that are in "phase two" of their development. These companies have made it through the proof-of-concept state (they know they have something that has commercial potential) and must now deal with practical barriers such as figuring out how to build and test prototypes, setting up a business, complying with regulations, and finding investors. "How do we help them find funding and get them scaled up? We can solve a lot of hard problems by getting people from different disciplines to take part," Williams says.

The southern Willamette Valley already has an active investment community, and the 2013 Willamette Angels Conference (an annual competition for entrepreneurs to win funding) had a huge year in terms of investment, Williams says. "Now we need to find ways to leverage the investments and attract others," he says. "Combining resources in Eugene-Springfield, Albany, Corvallis, and both universities gives us the critical mass to find capital. More investors will come in when they see the quality of investment opportunities here."

A seasoned supporter

Mike Marusich arrived at the University of Oregon in 1981 as a postdoctoral research associate and established the University of Oregon Monoclonal Antibody Facility in 1988. He directed the facility for 20 years and created a large number of monoclonal antibodies used as research tools by UO investigators. Many of these antibodies were also licensed out by the UO to biotechnology product distribution companies, making them available to scientists worldwide.

In 2004, Marusich cofounded a spinoff biotech company with Rod Capaldi, former Knight Professor of the Arts and Sciences and member of the UO's Institute of Molecular Biology. Their company, MitoSciences, develops mitochondrial antibodies and assays used in basic cell biology research and to create screening tests for cancer, neurodegeneration, and metabolic disorders.

Marusich and Capaldi put together a lab in the Riverfront Research Park, incubated MitoSciences there, and eventually sold the company in 2011. Although the founders left the company after the sale, MitoSciences has stayed in Eugene with the rest of the team intact and now has more than 30 employees—it's one of a number of UO spinouts that generate royalties for the university through intellectual property and materials licenses and agreements. "It's a success story both for UO and for the region," Marusich says.

Having a resource such as RAIN would have made the company's research-to-business transition easier, he says. "We had to figure the business side of things out for ourselves, and we had to put together a lab where there wasn't one. Those were difficult problems unrelated to our research and product development, and it would have been very useful to have had a more established business track to follow."

For new ventures, RAIN's network of soft support will offer help with accounting, health plans, insurance, marketing, business plans, and more. Besides that, "it will be terrific to have a place where there is a whole group of entrepreneurs together—like-minded individuals—so you are not isolated," he says.

Marusich has a new company, mAbDx, Inc., that is focused on identifying biomarkers and diagnostic tests for cancer and inflammatory diseases. The company is independent from the UO, but is renting lab and office space in the university's new Lewis Integrative Science Building—one of two "partnership spaces" that give researchers from the private sector access to high-tech tools and equipment and the ability to interact easily with UO researchers.

At mAbDx, Marusich is working to develop a simple, noninvasive saliva test for early diagnosis of head and neck cancers—the sixth most common cancer in the United States. The test uses monoclonal antibodies to detect and measure levels of a specific cancer protein—a biomarker—discovered by Oregon State University College of Pharmacology professor Mark Leid, who is collaborating with Marusich on the work. Another project is a collaboration with PeaceHealth infectious disease specialist Dr. Robert Pelz to detect biomarkers and create rapid diagnostic tests for sepsis, a potentially fatal inflammation of the whole body that kills more than 200,000 people in the United States every year. Marusich is also working in collaboration with Harvard trauma surgeon Carl Hauser to identify biomarkers and develop early tests for life-threatening systemic inflammation that can arise following trauma, even in the absence of infection. After trauma, damaged cell materials can be misrecognized by the immune system as dangerous bacterial or viral invaders. "We are working to discover the key drivers of this process and create diagnostic tests to identify those trauma patients at risk of severe inflammation," he says.

Marusich plans to be integrally involved with RAIN as he develops his new venture. "I want to be available for other people in the network and share what I have learned," he says. "However, I still have a lot to learn and expect to benefit myself from interactions with a wider network of experienced colleagues."

A multitude of resources

The UO already offers a number of programs designed to help entrepreneurs get a successful start.

Innovation Partnership Services, formerly known as Technology Transfer Services, licenses and manages the university's intellectual property portfolio, drawing up agreements between researchers at the UO and those who adopt their research.

The UO collected $7.9 million in 2012 from licensing university-developed technologies, while its spinoff companies generated $35.75 million in revenue during the 2011–12 academic year and employed about 250 workers.

Once there is a license for the new technology, Williams says, the work is not over. While the company may have received a federal grant for its research, procuring the funds to bring the research to market is often much more difficult.

Finding investors who are a good match is essential, he says, noting that they need to be passionate about what a company is doing and ready to open doors. Through RAIN, entrepreneurs will be able to ask the right questions, find mentors and business contacts, and know that people are working to support their success.

Williams also sees RAIN as an invaluable asset for getting companies to the point where they can pull in investment dollars or be acquired. Established companies often are not willing to just pick up technology, he says. "They want to acquire a company and a team that already works."

The UO's Lundquist Center for Entrepreneurship offers many resources. Under the auspices of the Business Innovation Institute at the Lundquist College of Business, the center (led by Nathan Lillegard '98, MBA '06) helps entrepreneurs bring their ideas to market, offering expertise in early stage finance and operations, technology transfer, and more.

A number of programs fall under the Lundquist Center's umbrella, including the Technology Entrepreneurship Program (TEP), which facilitates the transfer of science-based technology from the lab to market. Lillegard's former company, Floragenex (a genomics research company), was a "sprout" of the TEP program. "The UO gave us support on all sorts of fronts," he says. In its early stages, Floragenex received a Venture Launch Grant (grants that provide seed funding to help startups generate their first products and services) of $50,000 and then the UO helped the company procure a grant of $250,000 from the Oregon Nanoscience and Microtechnologies Institute (ONAMI), which, among other services, offers "gap" grants to startup companies with high growth potential. Floragenex incubated in the Riverfront Innovation Center for five years and now has locations in downtown Eugene and in the Oregon Bioscience Incubator in Portland. The company, with four full-time employees, provides its technology primarily to academic researchers in about 20 countries. While Lillegard is no longer involved, "Floragenex is steadily and profitably growing," he says.

Another resource for RAIN is the Innovation and Entrepreneurship Program, also at Lundquist, which brings together science students with students from the Lundquist Center and the law school's Center for Law and Entrepreneurship. The teams work together to bring research through the proof-of-concept stage and help with legal and business issues relating to starting a new business.

A third program is the Strategic Planning Project, the capstone of the MBA program. Here, teams of students are matched with real-world business partners, whom they help with market research, data analysis, and more.

One of the most positive aspects of RAIN is that it will connect all of these vibrant UO resources with others in the community, Lillegard says, and indeed, RAIN has strong backing outside the two universities. "We're all in this together," says Eugene Mayor Kitty Piercy, who, along with Corvallis Mayor Julie Manning will cochair the planning committee that gets the network up and running. "I hope this will open a door to strengthen our local economy, to grow more jobs that pay a decent income, and keep them here," she says. "I

really appreciate the effort that the UO has put into this."

Calden Carroll, MS '08, PhD '11

SupraSensor Technologies

Nitrate sensors for precision agriculture

Calden Carroll focused his graduate studies on supramolecular chemistry—the study of interactions between molecules. While working to create a dye that would follow chloride as it is shuttled in and out of cells (to help determine how cellular mismanagement of chloride can lead to cystic fibrosis), he realized that he had discovered a marker specific for nitrate. "I spent all that time and it turned out it wasn't specific for chloride at all," Carroll says.

But as he defended his dissertation (he did eventually find the marker for chloride), someone in the audience noted that soil nitrates are extremely important in agriculture—his earlier work might have some unanticipated value. "Dirt wasn't first on my list of things to study," he remembers thinking.

But as he soon learned, dirt is pretty darned important. The National Academy of Engineering has identified managing the nitrate cycle in agriculture as one of 14 "Grand Challenges" in the 21st century. Originating in synthetic fertilizers and animal manure, nitrates wash out of the soil, creating algal blooms in lakes and streams and polluting drinking water. "It would be better to systemically stop the input instead of cleaning up the output," Carroll says. "Nitrates are very mobile. Farmers should know exactly where they are."

And that's what SupraSensor Technologies is all about. The company is in the early stages of manufacturing a nitrate-sensing probe—based on Carroll's original research—that is designed to help farmers optimize fertilizer usage and minimize environmental impacts. The sensor precisely measures nitrate levels in the soil and then sends that information wirelessly to the farmer's computer, enabling real-time monitoring of fertilizer application—with the potential for dramatically reducing the amount applied.

When Carroll's research team (which included UO chemists Darren Johnson, Michael Haley, and Bruce Branchaud) brought their new product to the National Science Foundation's Innovation Corps in 2012, they won first place out of 25 teams from all over the United States. "That snowballed into a Small Business Innovation Research grant that funded us to do proof of principle—to show that we can create a molecule that can test for nitrate in the soil," Carroll says.

SupraSensor, whose leadership includes Carroll as well as founding member August Sick (formerly of Invitrogen and Life Technologies), next received a "gap grant" from ONAMI that allowed them to develop the instrumentation needed to make the nitrate tester. Currently, they are working on scaling up production—making a few hundred sensors so they can test them in various soils around the state.

As the company was first developing the sensor, they were able to get advice and mentoring from scientists and technology entrepreneurs at ONAMI and CAMCOR and to take advantage of fee-for-use laboratories at the university. "That gave us a head start on product development," Carroll says. "I had no background in running a business. I knew exactly where to find chemicals, but I was at a loss as to how find contract manufacturers who know how to scale up production."

Carroll says he wants to keep SupraSensor in Oregon despite the challenges of building a business here. He sees RAIN as a valuable resource. "It will create a knowledgeable community of business and technology pros who can help startups navigate the bureaucratic waters and prepare young entrepreneurs for all of the basic stuff that might get taken for granted by the old guys," he says. "It will also be great to have people who can help identify funding opportunities and affordable spaces for early-stage start-ups while they get their feet under them."

Carroll says his company still needs a lot of help from the business community. "We are moving fast," he says, "but there's the point when you have to jump across the 'Valley of Death'"—referring to the moment in a startup's development when it grows from a small team to a viable business. "Once you get past the 'cool science' part of it, and into the nuts and bolts of production, you need private capital."

Marshall Gause

Thought Cycle

Educational software for elementary school kids

Video game developer Marshall Gause got into designing educational software through a serendipitous door. One day he asked his next-door neighbor, Hank Fien, to help him move a piano. He and Fien, codirector of the UO's Center on Teaching and Learning (CTL), really hit it off and soon were "hatching these big ideas together," recalls Gause.

Out of the big ideas came Gause's company, Thought Cycle, which develops software in partnership with the CTL. "Our team does the engineering, art, and design, and the center provides the curriculum and the research," Gause says.

Thought Cycle's first product is NumberShire, an interactive game that teaches the concepts of whole numbers to kids in kindergarten through grade two. Underneath the engaging graphics and fun story line, NumberShire is a structured learning program geared toward students who are lagging a bit behind in math. Students take on the role of apprentice to an elder in a fairytale village. The elder is going to retire, and the apprentice is learning the ropes so she can take over. In the meantime, the two team up to help the villagers with various problems, progressing through the narrative while learning math along the way.

Thought Cycle got its first infusion of cash in 2010 with a Small Business Innovation Research grant that funded the development of the first-grade version of the game. NumberShire had a successful one-week test run in Boston classrooms and is currently in an eight-week pilot program in Eugene and Hillsboro.

"I wish RAIN would have been around when we started," says Gause, noting that he has worked closely with Chuck Williams at Innovation Partnership Services, as well as with a number of colleagues in the private sector, on licensing the software and bringing it to market.

The company has eight employees. "We are all pretty rooted in Eugene and we want to stay here," Gause says. "I think RAIN is a really great idea."

Allan Cochrane

Cascade ProDrug

Safer treatments for cancer

Entrepreneur Allan Cochrane and his business partner, August Sick, know a good idea when they see one. In November 2009, the two obtained the assets of a company that had developed technology to make anticancer medicines less toxic.

Cascade Prodrug's unique technology renders chemotherapy drugs inactive when they enter the body by loading them with extra oxygen. The drugs are designed to activate in low oxygen conditions (such as can be found in tumors) and the company is testing to analyze this hypothesis. This method of design could deliver a more effective therapy as well as one that's safer and more tolerated.

The technology was originally developed by UO chemistry professor emeritus John Keana and is licensed by the UO. Besides being a stakeholder in Cascade Prodrug, the university helped the company obtain financing. "I would rate the scale of our relationship with UO as a 10," Cochrane says, adding, "We still come back to the UO for basic science and research."

Cascade Prodrug's first round of financing raised $1.4 million, with the initial investment coming from the Oregon Angel Fund in Portland. That vote of confidence attracted more investors, and to top it off, the company won first prize at the 2012 Willamette Angel Conference, garnering about $220,000 from local investors.

Besides running the company, Cochrane is an adjunct management instructor at the UO, where he teaches the New Venture Planning course for MBA students. He also helps new companies get off the ground by offering coaching to early stage CEOs.

"In our local community, entrepreneurship is fairly embryonic," he says. "It needs structure and maturing, but there is the backbone and interest in the community to get it going. Hopefully, I can be one of those people who help. It is pure enjoyment for me."

—By Rosemary Howe Camozzi

Rosemary Howe Camozzi '96 is editor of Oregon Coast magazine. She is a frequent contributor to Oregon Quarterly and writes for a number of other regional and national publications.