Like many expansive research projects, the one Steve McKeon '00 recently conducted started out with a simple observation.

In the early 2000s, McKeon was applying his UO degree in finance at a large winery in Napa, California, eventually becoming its CFO. He interacted with numerous CEOs of other wineries, many of whom had strong personality traits that were, it seemed to McKeon, reflected in how they guided their companies. In general, executives who appeared cautious and conservative by nature seemed to run their businesses in a circumspect manner, while CEOs with more flamboyant personalities were more likely to take chances in the boardroom.

No Stranger to Risk Steve McKeon wears an oxygen mask while flying in a twin-engine Cessna around the summit of 20,000-foot Mount McKinley in Alaska.

"'Behavioral consistency' is the technical term we use to describe this connection," McKeon says.

He left the wine business in pursuit of a doctorate in finance from Purdue University. There he casually shared his observation about CEOs with fellow student Matthew Cain. The two wondered if the link between personality and business behavior might also apply to the captains of American industry—whose decisions could make or lose their companies and stockholders billions of dollars.

With such vast sums at stake, it is easy to understand why research into CEO characteristics has a long history. But most of this work focused on such obvious factors as age, birthplace, height, education, and even, as presented in a 2013 study from Duke University's Fuqua School of Business, the pitch of male CEO voices.

McKeon and Cain were after insights based not on such easily obtainable information but on the subtleties of human psychology. They searched for a measure of both personal and professional behaviors. The answer was an executive's willingness to put self and company in risky situations.

"We thought of all kinds of metrics for personal risk-taking," McKeon recalls. "We considered speeding tickets, motorcycle riding, skydiving . . . but a database of, say, skydiving CEOs simply does not exist."

The Federal Aviation Administration, however, does maintain an accurate list of Americans with a private pilot's license. Such flying—more than 300 times more likely to result in death than traveling by commercial airliner—is a good proxy for personal risktaking (see graph below).

"That was the major breakthrough," says McKeon, who returned to the UO three years ago as an assistant professor of finance in the Lundquist College of Business.

The researchers matched the FAA roster of pilots against the names of the chief executives of America's biggest corporations and found about 180 CEO-pilots who could be compared with a control group of 3,000 nonpilot CEOs. They then began the work of gathering vast amounts of data about each CEO's corporate performance and subjecting the data to rigorous analysis.

When all the numbers were crunched, McKeon and Cain (now an assistant professor of finance at Notre Dame) wrote up their results in a paper titled "CEO Personal Risk-Taking and Corporate Policies," currently under review at the Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis.

The research shows that CEO pilots exhibit substantially different business behaviors than their nonaviator counterparts—differences that reflect an increased willingness to take on risk. Pilot-CEOs tend to guide their companies to incur more debt, as well as execute more mergers and acquisitions. Their company stock prices show greater volatility. And they are more likely to be paid with options and equity-based compensation, indicating a higher level of confidence in their own company's future performance (see graphic below).

"Everyone wants to know if these findings are good or bad news, and what they might say about investing in companies run by risk-taking CEOs," McKeon says with an understanding smile. Perhaps the most surprising thing the research reveals, he says, "is that there is no evidence these CEO behaviors are detrimental to their companies' performance." There is a fine line between confidence and overconfidence, he points out. "Just because an executive is willing to tolerate a higher level of risk does not necessarily make that executive overconfident."

For many people this is counterintuitive, especially in light of the devastating global recession of recent years, caused at least in part by boardroom miscalculations of risk.

Nevertheless, McKeon says, "Risk-taking is the basis of business. It does not equal recklessness."

Work Hard, Play Hard

The desire to fly an airplane has been shown to represent one aspect of a sensation-seeking personality, a genetic trait associated with risky behavior involving

driving, sex, sports, and vocation.

—"Executive No-Fly Zone?" Wall Street Journal

Some titans of industry famously thirst for thrills.

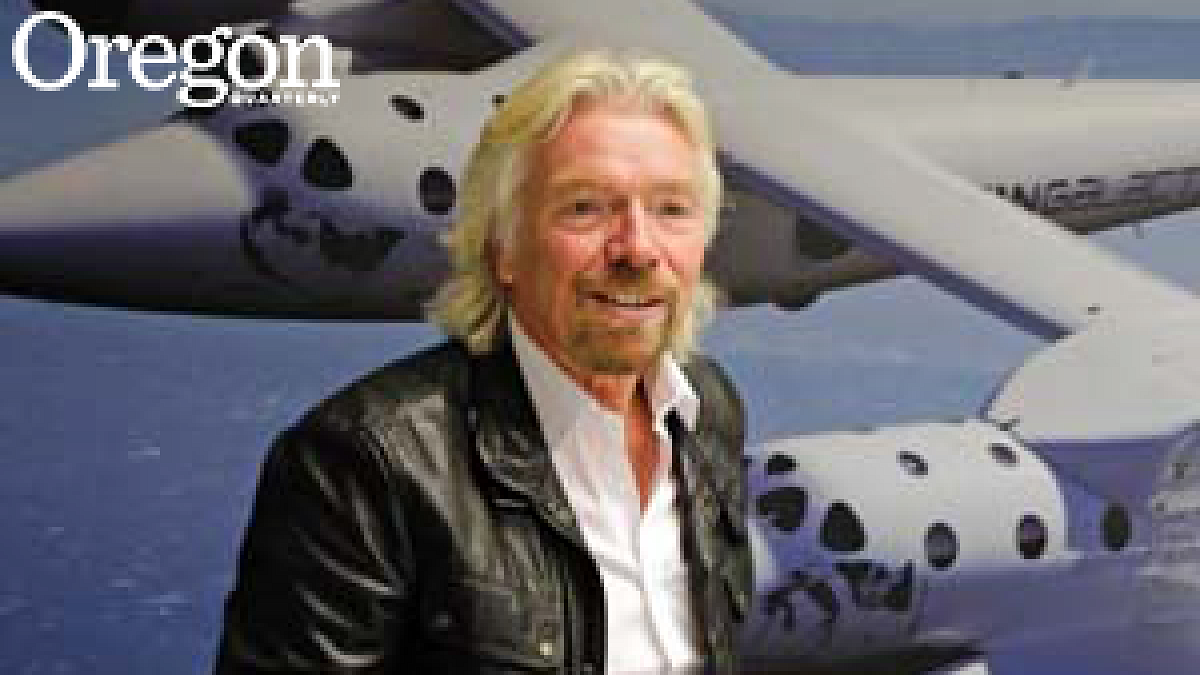

Virgin Everything's blond-locked Richard Branson is a legendary adrenaline junkie; his risky exploits have resulted in life-threatening boat crashes and, while attempting the first trans-Atlantic balloon flight, a near-fatal plunge into icy Scottish waters.

When away from his desk at Oracle Corporation, mega-billionaire Larry Ellison likes to fly planes—among them his own Russian-built MIG-29 fighter jet.

But sometimes, as the odds dictate, risk takers pay the ultimate price.

Micron Technology CEO Steve Appleton —a martial arts practitioner, motorcycle racer, and monster-car driver—fatally crashed his single-engine airplane in early 2012. "I'm obviously an aggressive person," the 51-year-old microchip mogul prophetically told a Wall Street Journal reporter. "It is kind of a cliché, but I'd rather die living than die dying."

A father of four, Appleton credited his risky diversions with sharpening his decision-making skills. He once likened himself, in the Business Times of Singapore, to the super speedy, bullet-dodging hero of the film The Matrix, adding that the computer memory business is "in slow motion in comparison to all the other things I do."

—By Ross West, MFA '84