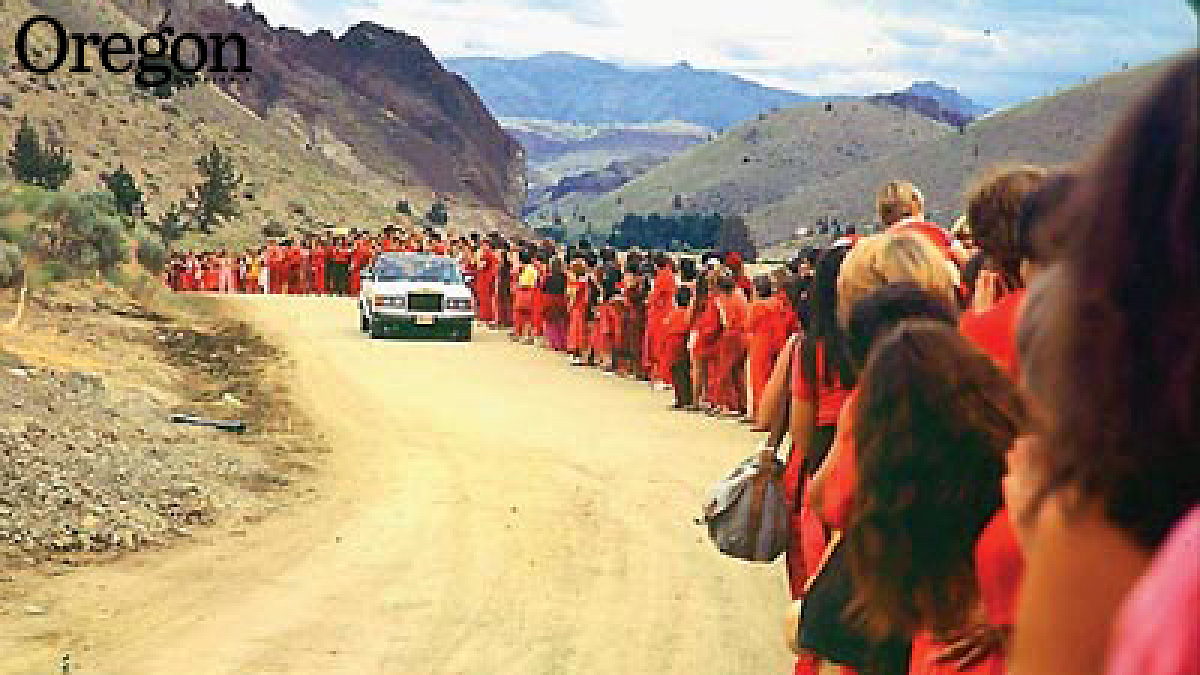

A plague of Biblical proportions came perilously close to being loosed upon the Earth from a secret laboratory in the north-central Oregon compound of religious leader Bhagwan Shree Rajneesh. The lab did succeed with its cold-blooded plot to indiscriminately poison local residents, affecting more than 750. These and many other stories are related in The Rajneesh Chronicles: The True Story of the Cult That Unleashed the First Act of Bioterrorism on U.S. Soil by Win McCormack, MFA '78 (1987, 2010, reprinted by permission of Tin House Books, Inc.). The book is a collection of reports he wrote between 1983 and 1986 for Oregon Magazine; its introduction is excepted below.

The goings-on at this so-called commune were deadly serious, for it was there that the first act of bioterrorism in U.S. history—salmonella poisoning of citizens and officials of Wasco County—was plotted and launched. . . .

In his book To an Unknown God: Religious Freedom on Trial, legal scholar and former Washington Post reporter [and formerly the UO’s Orlando and Marian Hollis Professor of Law] Garrett Epps correctly identifies the two stages in the Rajneeshees’ assault on their perceived enemies in the outside world. The first stage involved the poisoning with salmonella bacteria of restaurant patrons in The Dalles, the Wasco County seat, in September 1984, in a test run of one component of their plan to take over the county government in the fall election: disabling opposition voters and preventing them from going to the polls.

When that stage failed, they embarked on the second stage, a plot to kill various people on an enemies list they had compiled. This list included Charles Turner, the then-U.S. attorney for Oregon, who was supervising an investigation of them for immigration fraud and other offenses, and Les Zaitz, an Oregonian reporter [and former Oregon Daily Emerald columnist and editor] then engaged with two colleagues in an extensive journalistic investigation of the cult spanning three continents. It was assumed at the time that the principal objective of Zaitz’s investigation was to nail down proof of the Rajneeshees’ direct involvement, abroad as well as in the United States, in more serious criminal activities, such as drug and currency smuggling and possibly even more sinister crimes.

In his chapter detailing the criminal evolution of the Rajneesh cult, entitled “East of Eden,” Epps’s central focus is on then-Oregon Attorney General Dave Frohnmayer, one of two main subjects of Epps’s book, which deals with various conflicts between church and state. Frohnmayer had also made the Rajneeshees’ enemies list, as a result of the lawsuit he filed calling for the dismemberment of Rajneeshpuram on the grounds that the intermeshing of Rajneesh’s religious foundation and the operations of the city violated the Establishment Clause of the U.S. Constitution. Frohnmayer began his official attorney general’s opinion on the matter with a “sweeping discussion of religious freedom and the demands of a liberal, secular, democratic order in America.” In America, Frohnmayer wrote, “[t]olerance is not merely a moral virtue; it is a matter of constitutional policy.”

The story of the Rajneeshees in Oregon does raise serious questions about liberal democratic tolerance, and its advisable limits, far beyond the purely religious one. The seeming inability of various governmental entities to deal effectively with the numerous infractions and misbehaviors of the group—its skirting of Oregon’s land-use regulations and the land-use permits it was granted; its flouting of immigration law through obviously bogus marriages between foreign and American sannyasins; its systematic and cruel persecution of the residents of the nearby town of Antelope, of which it had taken control as a fallback if the city of Rajneeshpuram were declared illegal; its arming of commune residents with semiautomatic weapons while its leaders were issuing threats of violence against the surrounding community and law enforcement—suggested a bewildering and alarming paralysis in the American and Oregon political systems.

Such issues are explored in a 1987 senior thesis entitled “Antelope, Oregon and the Need to Revise Liberal Democracies,” by Rolf Christen Moan, a student in Harvard College’s social studies department whom I had the pleasure to advise on his project. My own analysis, which I freely offered him (as a former student in the government department there), was that the American political system is so fragmented, first between the national and local levels, and then, at each level, between different branches of government and entirely separate departments, that no one entity or political leader or official had the overall authority to confront the fundamental challenge the Rajneeshees presented. . . .

Another Harvard senior thesis of relevance here, also involving issues pertaining to the success or failure of liberal democracy, is “Four Types of Elitist Theory: Bentham, Nietzsche, Lenin, Mosca and the Elite in Liberal-Democratic Thought,” submitted to the government department in 1962 by David Braden Frohnmayer (it received a grade of magna cum laude, as did Moan’s). Twenty-four years after that submission, Frohnmayer, attorney general of Oregon, was asked by a reporter whether he thought Bhagwan Shree Rajneesh had sanctioned the poisonings his henchwomen carried out. Frohnmayer replied that his familiarity with the ideas of Nietzsche, which he dissected in his senior thesis, had helped him understand Rajneesh’s philosophy: “His philosophy is not incompatible with poisoning,” Frohnmayer said. . . .

In her book Germs: Biological Weapons and America’s Secret War, published in 2001, Judith Miller devotes the first chapter, “The Attack,” to the Rajneeshees’ bioterrorism schemes. Relying heavily on information provided to the authorities in 1985 by David Knapp, aka Swami Krishna Deva, ex-mayor of Rajneeshpuram, and Ava Kay Avalos, aka Ma Ava, a lab assistant to Ma Anand Puja, the Filipina nurse who oversaw the Rajneesh Medical Corporation and its bioterrorism program, Miller carefully reconstructs the project’s insane progression.

Before Puja, known at the ranch as “Nurse Mengele,” and Ma Anand Sheela, Rajneesh’s top assistant, decided on Salmonella typhimurium, a common agent in food poisoning, as the means to incapacitate voters in Wasco County, they contemplated using much more dangerous substances. These included Salmonella typhi, which causes often-fatal typhoid fever; Salmonella paratyphi, which causes a similar, less severe illness; Francisella tularensis, which causes a debilitating and sometimes fatal disease, and which was weaponized by U.S. Army scientists in the 1950s and is on the Pentagon’s list of agents that might be used in a biological-warfare attack on the nation; and Shigella dysenteriae, a very small amount of which can cause severe dysentery resulting in death in 10 to 20 percent of cases.

Puja placed orders for these pathogens on September 25, 1984, just as the Share-A-Home program to import thousands of street people into Rajneeshpuram to register them to vote in the coming election was gearing up. She also ordered antipsychotic drugs such as Haldol to control the street people while they were at the ranch. And she contemplated putting dead rodents—rats, mice, beavers—in the county’s water supply to sicken the populace. She apparently had particular confidence in beavers, because they carry a natural pathogen, Giardia lamblia, that causes severe diarrhea. Giardia lamblia had been prevalent at the Rajneesh ashram in India.

As related in [this book’s chapter] “Bhagwan’s Final Year” and in the afterword, “How Close Was Disaster?” when authorities raided the Rajneesh Medical Corporation after the Bhagwan’s September 16, 1985, press conference denouncing Sheela, they found the following books: Handbook for Poisoning; How to Kill; Deadly Substances; The Perfect Crime and How to Commit It; and Let Me Die Before I Wake. They also found articles on infectious diseases, chemical and biological warfare, assassinations, explosives, and terrorism.

Krishna Deva reported to authorities that when Sheela asked their “enlightened master” what should be done about people who opposed his vision, Rajneesh compared himself to Hitler and stated that Hitler had also been misunderstood when he sought to create a “new man.” Rajneesh informed them that Hitler was a genius whose only mistake was to invade Russia . . . .

How much farther . . . might the Rajneesh cult have traveled, if its course had not been interrupted? . . . At one point in her narrative, Miller focuses on the aspect of the Rajneesh story that has most haunted me for the last twenty-five years: the program to isolate a live AIDS virus that was underway in the biological-warfare laboratory at the ranch when the commune fortunately collapsed in the fall of 1985.

“Puja was also particularly fascinated by the AIDS virus,” Miller writes, “about which relatively little was known at the time. The Bhagwan had said that the virus would destroy two-thirds of the world’s population. For Puja, it was a means of control and intimidation. She repeatedly tried to culture it for use as a germ weapon against the cult’s ever-growing enemies. Her apparent failure was not for lack of trying.”