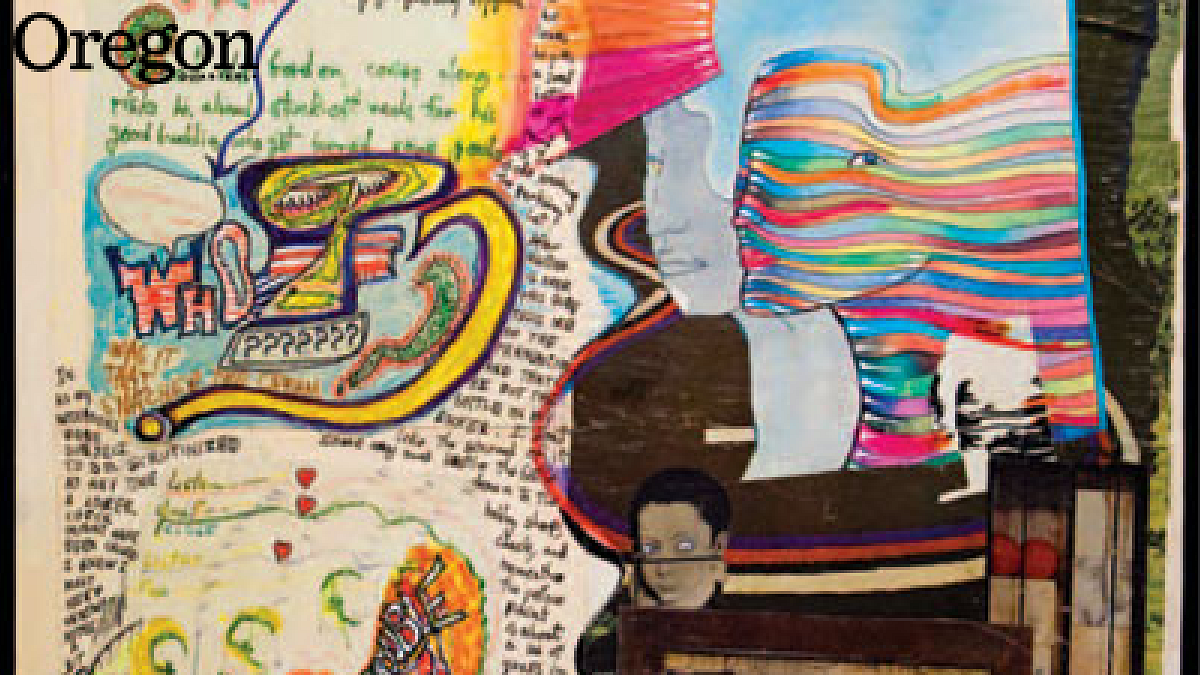

Ken Kesey ’57 chose to deposit his papers for safekeeping in the UO’s Knight Library Special Collections and University Archives beginning as far back as 1966. The collection now includes a vast stock of documents he generated from 1960 until his death in 2001: more than 100 boxes of manuscripts, artwork, collages, photographs, audio tapes, and correspondence. The UO has the opportunity to purchase the collection to make it a part of the library’s permanent holdings. If that doesn’t happen, the documents might leave the state of Oregon—acquired by another university or divided and sold into private hands. The final disposition of the Kesey papers is expected to be decided soon. For more information about the collection and to learn about how to help keep it at the UO, go to www.libweb.uoregon.edu/giving/kesey.html.

In the meantime, we present a sampling of excerpts taken from the collection. Italicized entries are from hand-written documents.

Working in the hospital

Can you believe it? Working full time for the first time in two years! The depths to which I have sunk are undiscernible.

Right now—or from 7:30 to 4—we are completing the four weeks of training at the hospital, with discarded texts and disregarded nurses. The first two weeks were spent on what is called the circle wards, or the better wards, wards where the men have enough marbles left to choose up sides and play the game, but these last two weeks we are being subjected to the vegetables, the geriatrics, the organs eating and organs shitting and pissing and moaning and coming on in religious tongues, creatures that need spooned puree and pablum, infants growing backwards, away from civilization and rationalization, back to complete dependence, to darkness, the womb, the seed . . .

Around the day room. All twisted out of shape by so many years. Ellis: with whatever it was that frightened him absolutely out of his mind, standing right before his aghast eyes, still gaping, horrified, outraged, and farting in his fear. Bewick: his face showing only a gnawed dissatisfaction, gnawed so deeply that he is finally and forever even dissatisfied with that, and only whimpers tearlessly. Pete: grinning, shaking his happy old head, limping spryly about in his pajamas, answering only one question—“Why’d you quit driving the truck, Pete?” “I was ty-urd. Fo’ tweny eight years, then I got ty-urd.”

Like old Buckly, who asserts, or answers when asked: “We had some fun, didn’t we? Sure, we gone have lots of fun.”

Or old Chartes, whose trigger question is “How is your wife?” and whose screamed answer is “F-f-f-uh thuh wife! F-f-f-k theh wife!”

You get to know them by their bits.

Maternick is tidy, is his bit. No one can touch him. He won’t touch an object another has touched. He strips if a towel touches him. He rubbed the hide off the end of his nose once after running it up against a patient who had stopped too quickly. He is tall, stooped, eyes lost under a cliff of a brow, rubbing his hands forever together, looks like an old time wrestler I saw once called the Swedish Angel. And he coughs violently whenever he smokes his daily allotted cigarette. “The smoke . . . dirty!” But he begs continually for cigarettes.

Writing as religion

Writing becomes more and more a religion with me as I realize more and more that this is what I’m going to be doing all my fucking life. (Make money any other way I can . . .) And until you completely relinquish yourself to this fatalistic inevitability your work cannot, in your own mind, rise to the importance it deserves.

Getting published

I just received and read my book. My book. You’ve got no idea what that phrase evokes. A cavalcade of pinwheel emotions. All the old, spangled, bright, and gaudy and (I love them) cheap emotions of the ego realizing its muscle and mind—the notions of fame, the flamboyant fantasies of parties in New York penthouses, skinny women with red capris and silver eye shadow leaning and coaxing from a satin bedroom, my portrait on the cover of Time looking stern, wise, and sexy—all of these daydreams that one toys with early, knowing that they must be toyed with early because (knowing this too, when pressed) there will come a time when they will have happened, or are never going to happen and daydreaming is no more fun because it is either remorse or nostalgia (which is candy-coated remorse).

The very weight of the book activating anew these old fireworks, along with one rather gloomy newcomer: A sudden, surprised self-consciousness and doubt, much like the self-consciousness and doubt that strikes a small boy who has been shouting, singing, turning elaborate conniptions to catch the attention of the world around him and realizes all at once that he has succeeded by some clever feat and lo! people are paying attention to him; what he says next must be weighed with a great deal more care than he gave to his previous demonstrations. He clears his throat, swallows, stands straight, and somewhat pompous . . . and lacking the desperately free enthusiasm of his boyhood proceeds to bore the hell out of his listeners.

Scribble #3

I reached the cigarette across to her and though the length of her arm would easily bring her hand to mine, it didn’t quite make it, and her hand groped a little asking me to make just a little more effort. These things do happen, don’t they.

Letter to John F. Kennedy

President Kennedy:

As one jock to another I’d like to point out that we are involved in a very weird game, where advances are made without possibility of touchdowns, where everybody bets at once and an error, or a knockout, is fatal to all opponents and the rounds, or the innings, are scored with the point system by millions and millions of judges. Our children will tally the final score.

To effectively play the game it is important to be continually aware of the attitude of all those judges, as well as their criteria for awarding scores or penalties: yards are lost each time a team advances, a foul is declared for not hanging on in the clinches, and a bean ball can cost a team the game. The penalty rules are severe but subtle and that which might at first look like a successful attack turns out to be a fumble. It is therefore safer, though maybe not so flashy, to stick to the bread-and-butter plays: yards are gained for every hungry man fed, for every sick man healed, for every captive man freed; points are scored for significant retreats from the line of scrimmage, and the game is always subject to be called at any time on account of peace.

I just thought I’d take the liberty to clear up some of these fundamentals with you; as always, chances for victory will be greatly enhanced by simply knowing the rules and keeping an eye on the ball.

Ken Kesey

The Push

The point of plot being, naturally, to have one player carom off the second, bounce in precise pattern from one, two, three cushions, and go on to strike the third. It can all be calculated in advance by an electronic brain, and set to formula, needs only an exact push in a preconceived direction to bring about certain and irreversible results.

The trick is: the push. And even confined within their strict frame my dreams are still helter-skelter clatterings because of that one imponderable: the push.

On Finishing Sometimes a Great Notion

Finished my book and ran the bastard off the premises at pencil-point, sick to death of the sight of it and convinced that I have spent two years concocting from my crucible the most glorious, spectacular, outrageous, and super-colossal failure since Spartacus.