With a jolt, I’m awake. So are my sorority sisters out here on the second-floor sleeping porch of the Gamma Phi Beta sorority. It’s 2:00 a.m. in May 1951. Something is wrong. We crowd and jostle to get to the windows. On the lawn below us a crooked, flaming cross throws sparks up into the ink-black sky. Shadows of men move about. Somebody yells. “Hey, nigger-lover. You like him?”

I feel cold as ice. I know why this is happening. I’m dating DeNorval Unthank, a “Negro” student here, at the University of Oregon. That burning cross is meant for me.

My heart slams. My mouth goes dry. I’ve got to call De. I tear down the hall to the telephone booth. I can’t remember his number. I hurry to my room and grab a notebook, return to the phone and dial.

He’s sleepy. “Yeah? What’s up?”

“A cross. Burning out in front. I’m scared for you and Chet.”

De and Chet, another Negro student, live in a small, cinderblock apartment two blocks away.

“Nobody’s been around here,” De says. “Are you okay?”

“Yes. But those men might . . .” Brutal racist acts flash through my mind. Men in hooded sheets. Negroes, burned, mutilated, and hanging from trees. “The Ku Klux Klan!” I say. “They could come to your place and . . . ”

“We’re awake and we’ll be fine. But, maybe you and I shouldn’t meet tomorrow.”

“That’s just what they want. I’ll see you at the Side at four o’clock.”

“Good. Okay.”

I hang up and go back out to the sleeping porch. The men have left. The flames have died. Embers along the arms of the cross glow like living things. I ignore the tight knot of girls who are chatting quietly and I return to my room.

It had rained earlier that evening and, while walking me home, De loaned me his green corduroy jacket. When I came in and hung it on the closet door my roommate said, “Get that thing out of here. It makes me sick to look at it.” Thank God she isn’t in our room right now.

I’m nauseated and goose-bumped. I wrap De’s jacket tight around my shoulders. I sit down and try to think. Last week two men sitting across from De and me at Seymour’s Restaurant downtown stared at us. Their eyes were sharp as knives. Were they members of the Ku Klux Klan? Had they burned the cross? Would De be the target tomorrow night? Or the next?

I don’t believe college boys did it. Before I met De, three months ago, I was dating a fraternity boy. I broke up with him, but he wouldn’t be behind such a despicable deed. Yet the burning cross brings into focus what I’m up against.

It’s customary for fraternity boys who come to the Gamma Phi house on Hilyard Street, north of Eleventh Avenue, to wait in the living room for their dates. De is not welcome. I usually meet him on the other side of the footbridge over the Millrace. Or we meet at the Side at Thirteenth and Kincaid, or at the Falcon, called “The Bird,” tucked in a stand of big trees west of Straub Hall. And when De walks me home he tells me goodbye at the far side of the bridge.

* * *

At dawn I shower and eat an early breakfast. The house president asks me to meet with her and the housemother at five o’clock this afternoon. This isn’t the first time I’ve been asked to meet with them. They have repeatedly asked me to stop seeing De.

I argued with them. How and why can anybody dislike other people because they happen to have dark skin? And what in God’s name do these folks have against De? From what I know, he’s an outstanding student who comes from an outstanding family. “Family” is very important to my Gamma Phi sisters. A girl’s father’s profession holds enormous weight in the sisterhood. A dad who is a prosperous and well-known doctor is considered at the top of the heap. De’s father is a prosperous, well-known doctor and these women object to me seeing this doctor’s son?

I refused to bend to their demands, and De and I continue to meet after class at the Bird, at Taylor’s, or at the Side.

* * *

On this day after the cross burning, I go off to class. Some of my classmates have heard about the incident. They ask me questions, all of which I’ve asked myself. They are supportive and concerned as to who did the vicious deed. Nobody has a clue.

* * *

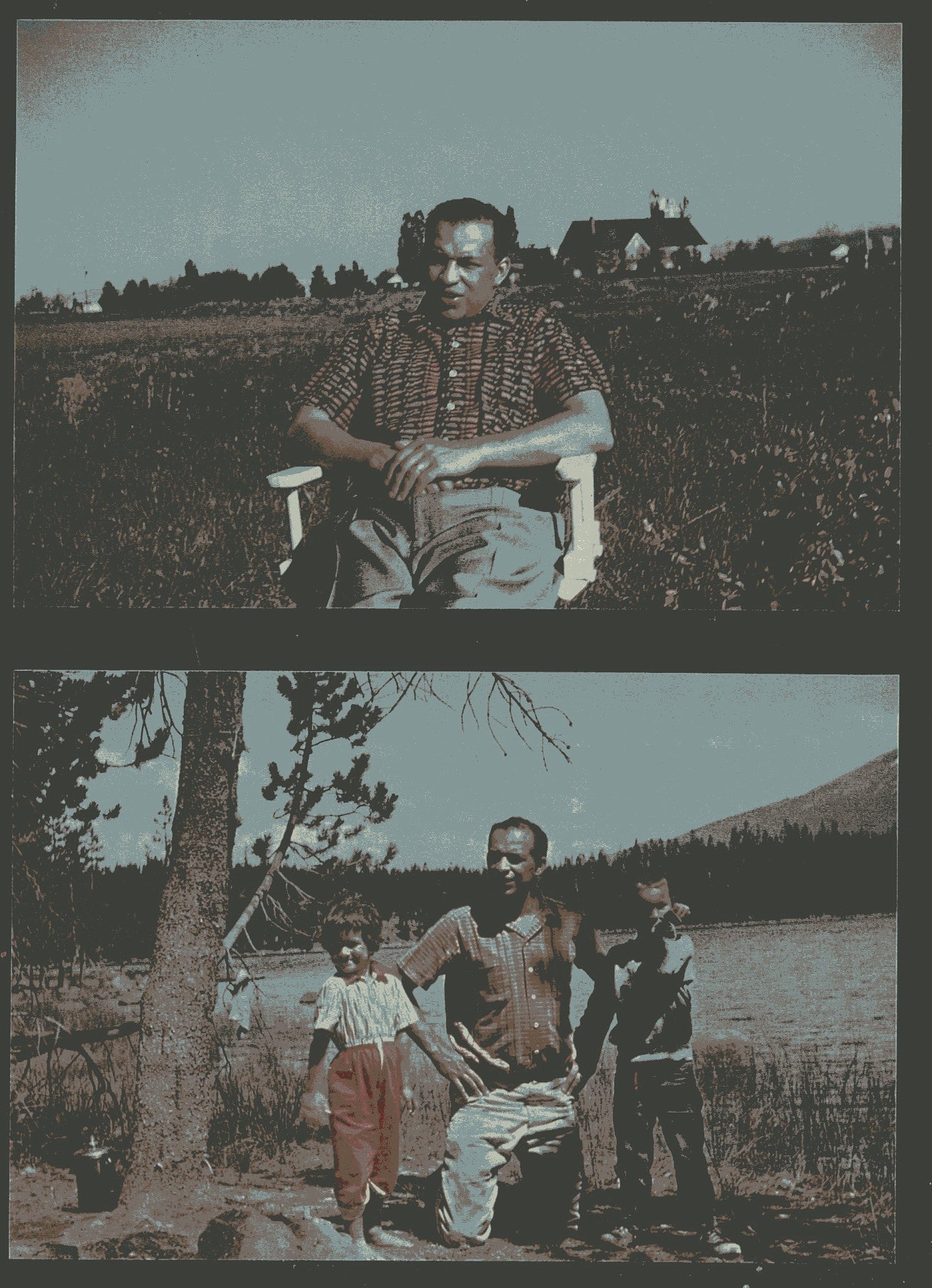

I met De in March of 1951 at an Episcopalian Lenten breakfast in Gerlinger Hall about three months before the cross-burning incident. I was a twenty-one-year-old sophomore majoring in anthropology. He was a fourth-year architecture student from Portland.

We all smoked cigarettes in those days and after breakfast he asked for a light. I snapped my lighter. It didn’t work. I tried it again. It failed. De took hold of my wrist and once more I struck the lighter. It sparked. He leaned back in his chair, smiled a lovely smile, and said, “Cigarette lighters know when to act up, don’t they?”

We laughed. “Where is your next class?” he asked.

“Friendly Hall. English lit.”

“I’m going to Lawrence. Can I walk you to class?” I liked this elegant, handsome man.

I learned that he had gone to Howard University in Washington, D.C.—a school I had never heard of. He loved jazz. Charlie Parker. Dizzy Gillespie. Sarah Vaughan. Foreign names to me. And he was passionate about the field of architecture.

In the early 1950s, positive things had begun to happen for Black people. In 1948, President Truman had desegregated the armed forces. As a senior in high school I wrote a paper about Blacks’ disinterest in intermarriage. But I knew next to nothing about Black people themselves. And as far as I knew, the few Negroes here on the UO campus were treated no differently than me or any other White student was treated. So if De were to come to my sorority house I assumed that my sisters would view him as an interesting, handsome young man.

My assumptions were naive, pitiful, and wrong.

* * *

It’s late afternoon and I hurry back to the house for the meeting. Barbara, daughter of the late UO president, Donald Erb, and a Gamma Phi alumna, joins us.

“I’ve never stopped seeing him.”

Once again, I’m told, “In our society, a Negro boy dating a White girl is not accepted. And the Portland alumnae demand that the house take action. If you continue to see that man, you will be asked to leave the house.” She paused. “But you will be welcomed back if you stop seeing him.”

I held my ground.

Then Barbara asks to meet with me and De the following afternoon. This is an ugly position to put him in, but I phone him and issue the “invitation.” He agrees.

The visit isn’t any different from the other meetings, except De is present. Barbara lectures us. “Debbie, your dating this man is having a bad influence on the house. If you don’t stop seeing him, the alumnae will step in.”

How in God’s name can this woman say these things in front of De? I marvel at his cool. He listens. He is polite. And after these people have done everything to make him feel unworthy and unwelcome, he still manages to leave the house with dignity.

I think about what they want me to do. I imagine this scenario: I leave the house. But I miss it. I miss “my sisters” and I want the prestige of being “a sorority girl.” So I break off with De. I’m welcomed back. Three cheers for me. I’m in good standing. Barbara is pleased. So are the alums. The girls are happy. Laughter bounces off the walls.

My imaginary thoughts overwhelm me with disgust. I have no attachment to these people. I don’t need them. I don’t want them. I won’t live here anymore.

The following day, I pack my bags and move into Hendricks Hall. After I’ve checked in and finished the paperwork, the housemother at Hendricks informs me that De can’t come inside. We argue. She reneges. But I make arrangements to move into an independent woman’s house on campus, for summer school.

De and I continue to see each other. On Friday afternoons, we meet at Max’s Tavern. We go to movies at the Mayflower Theater. Through De, I meet students of the arts—painters, architecture majors, and sculptors—including Tom Hardy, who one day would become famous for his sculptures. I meet poets and English majors. Discussions open a world of art, architecture, and jazz I’d never known. De’s friends become my friends. And De and I are in love.

In early June, I move into The Rebec House on Thirteenth Avenue. De is welcome to come inside. My roommate, Ruby Brock, is Black. She goes to summer school and is majoring in education. I’m working in the kitchen at Sacred Heart Hospital and going to summer school.

Ruby and I talk about the cross-burning. She says that I’m naive to think that racism doesn’t exist on campus, or in Eugene. Only six Black male students and two Black females are enrolled at Oregon. A number of Black families in Lane County live in the dumping grounds of a sawmill out on West Eleventh. No indoor plumbing. No sidewalks or paved streets. Racism is alive and thriving in Lane County.

And it’s still illegal for a Black person to marry a White person in Oregon. That law would change later in 1951. But in early July, De and I drive to Vancouver, Washington, and we are married in the Episcopal Church. Ruby is my maid-of-honor. Tom Hardy, our best man.

* * *

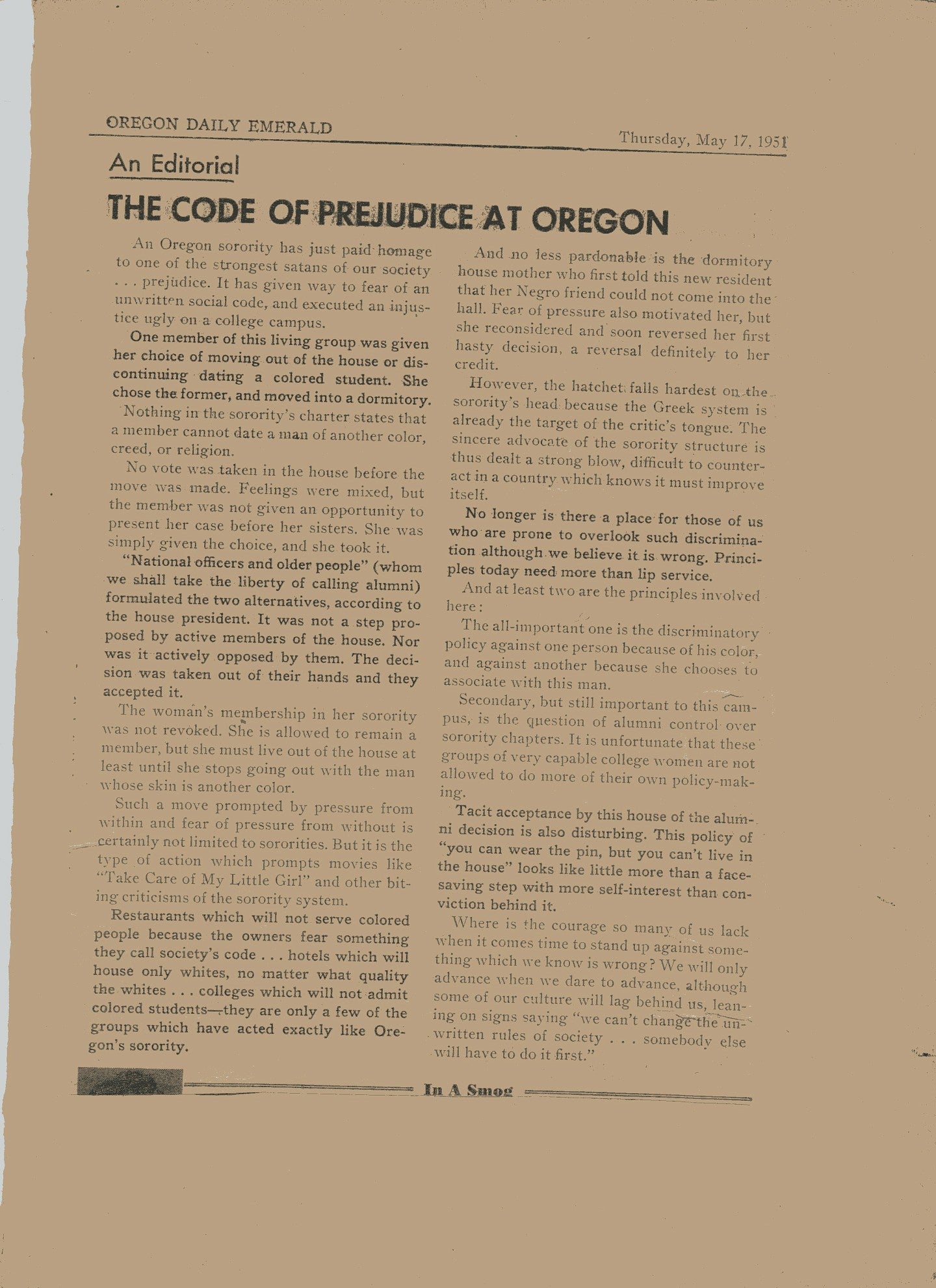

Now, in the summer of 2010, I pull out an old photo album of clippings and photos stored in a thick plastic wrapper and kept on a closet shelf. De’s late mother kept these things and I’m grateful. I wouldn’t have kept them.

I haven’t looked at them for more than fifty years. They are yellowed, fragile, and deeply creased. I sit down to read through them. It’s difficult. And I’ve forgotten many of the events surrounding De and me at that time.

I read in another publication about a representative of the Portland Gamma Phi Alumnae Association who asked me to sign a paper stating that I had “exercised” a free choice in deciding to move out of the sorority. The truth, as I recall is that I did so willingly and without a second thought.

On May 23, 1951, the Portland Journal ran an editorial. Harry K. Newburn, president of the UO, said that as far as the University was concerned, “one’s own friends are his own business.” But, the Journal pointed out the “disturbing” fact that no one among University authorities “seems to have made a serious effort to identify and reprimand the culprits who burned a cross on the sorority lawn in typical KKK fashion.”

The June 1951 issue of Time magazine took up the cry with an article titled Debbie and Gamma Phi, which stated “the Gamma Phi lawn [was] desecrated with a seven foot fiery cross.” And “finally the alumnae adviser had a quiet meeting with the errant pair and . . . urged them to stop seeing each other.”

After the ultimatum the sorority had issued me was exposed and condemned, the alumnae offered to let me return and I could continue to see De. I declined.

Today, as I read these clippings I wonder what kind of life I would have had if I had returned to that place. The thought defies my imagination. I was done with them and the racism that wrapped itself into what was “socially acceptable.” And I’ve never regretted the choice I made.

These hellish events occurred three years before Brown v. Board of Education, the Supreme Court decision that began the desegregation of public schools. How did the men who burned the cross feel when Brown became the rule of the land? In Money, Mississippi, August 1955, two White men mutilated fourteen-year-old Emmett Till, tied a seventy-five pound cotton gin fan around his neck, and threw him in the Tallahatchie River. Did the men who burned the cross in front of the Gamma Phi Beta sorority feel a prick of unease? And in December of 1955, when Rosa Parks’s courageous act of refusing to give up her seat on a bus set the stage for the civil rights movement, how did those men feel?

Perhaps they dismissed the years of the civil rights struggle. But in remembering that single, terrifying, degrading act, I’m angry. To my knowledge, nothing was ever done to try to identify those who burned that cross.

In the early 1960s a couple De’s and my age moved across the street from us. We learned that Mr. B., the husband, had been in school with us and was a fraternity brother of the young man I had dated before I met De. One evening, Mr. B. admitted that his fraternity was responsible for burning the cross. I have no proof if this was true and nothing more was said about the matter. De and I tried to put it out of our minds. We were busy raising our three children and leading our own lives.

I now live in Eugene, across the street from a slab of stone marking the site of Columbia College, founded in the 1850s. In 1859, Unionist faculty members urged Congress to admit the Oregon Territory to the Union as a free state as opposed to a slave state. The college was burned. Twice. It is assumed it was burned because of the liberal faculty. Congress admitted Oregon as a free state in 1859. At that time it would be another ninety-three years before a Black person and a White person could legally marry in Oregon.

De died in 2000. Our son, Peter, died in 2006. Our oldest daughter, Libby Tower, is marketing and public relations director at the Hult Center in Eugene. Amy Unthank, our youngest daughter, is the leader for the Forest Service’s National Fisheries Program and lives in Washington, D.C. Until I decided to write this article they knew very little about this disturbing event.

I’m now eighty-one years old and it’s been sixty years since that cross was burned on the Gamma Phi Beta lawn. Last fall a friend of mine urged me to write about the incident. I had been approached before, but had declined. I didn’t want to dredge up painful memories. Pain, because De is not here to review the facts, as I remember them to be. Pain, because nobody ever stepped up to the plate and admitted it. Pain, because I didn’t want my children to read about it. But after reading these crumbling articles of so many years ago, I decided to take it on.

Now, I carefully place all of the fragile, yellowed papers into the old scrapbook and I put the book back in the thick, plastic bag. I put the bag up on the shelf where it has been for some fifty years. I don’t know if I will look through it again. But the image of that burning cross, the sparks thrown up into the black sky and knowing why it happened, will be with me as it has been, for the rest of my life.

—By Deb Mohr