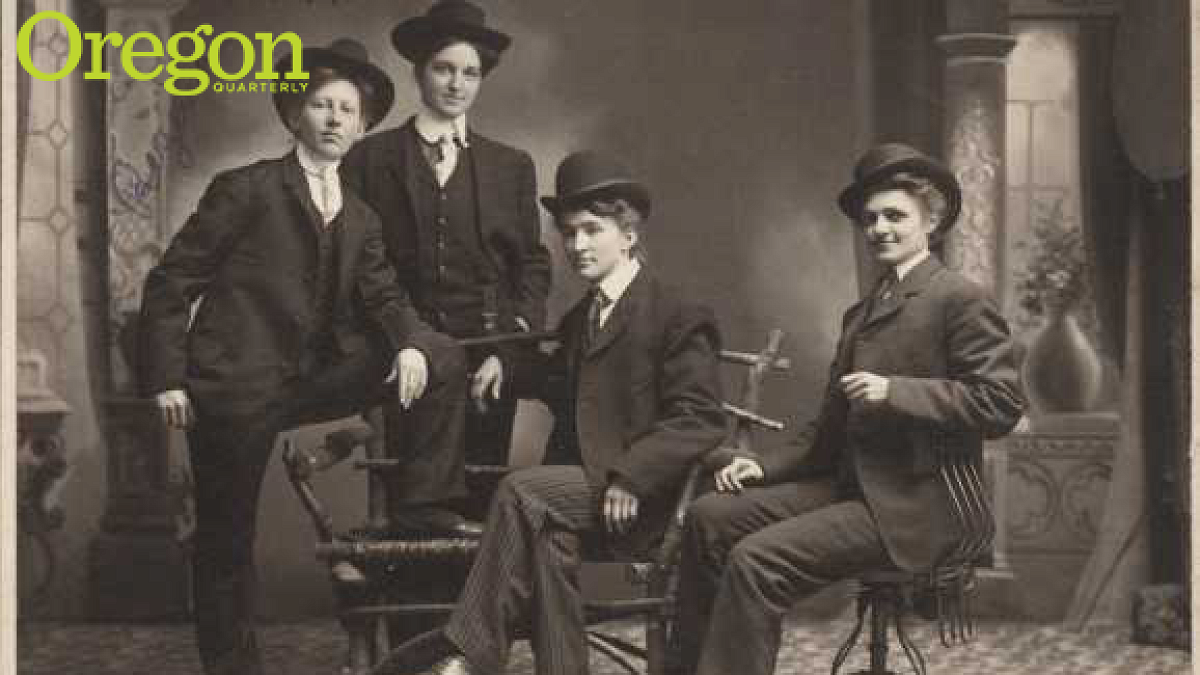

Americans have long cherished romantic images of the West and its colorful cast of characters. According to Peter Boag, PhD '88, who holds the Columbia Chair in the History of the American West at Washington State University, that cast of cowpokes and saloon keeps, farmers and ranchers, sheriffs and "soiled doves" might well also include cross-dressers, male and female. In his extensively researched Re-Dressing America's Frontier Past (University of California Press, 2011), Boag explores the historical and cultural setting of the time, recounts the stories of many of these western denizens, and discusses why they have largely faded from our collective memory of those much-celebrated days. One of these stories is excerpted below.

Most sources suggest that Joe Monahan turned fifty-three in 1903. By then he had made his home for almost four decades in and about the Owyhee Mountains of extreme southwestern Idaho. The last twenty or so of those years he resided on Succor Creek, a small stream that tumbles westward, down from the Owyhees, before it meanders out into the deserts of neighboring southeastern Oregon. In the last days of 1903, just as late autumn turned to early winter, Monahan contracted some unspecified malady. As he led an otherwise solitary existence, his enfeebled condition led him to seek refuge at the home of Barney and Kate Malloy, who lived just down a spot, on the Oregon side of the state line. . . . Unfortunately, as the new year arrived at the Malloy ranch, Monahan’s sickness only worsened. A virulent coughing fit overcame him during the evening of 5 January 1904. Sometime later that night, Monahan’s otherwise obscure life slipped away.

Similar stories—the sad passing of a weakened and relatively aged pioneer—were stuff of the everyday in the West by the turn of the twentieth century. But this tale turned out to be among the more newsworthy: when Monahan’s neighbors began to prepare his remains for burial, they discovered that their pioneer friend had the body of a woman. Troubled by exactly what to do, they administered a rather perfunctory funeral. A local from nearby Rockville, Idaho, who had for some time known Monahan, later wrote in dismay to a Boise newspaper when he learned about how Monahan had been treated in death. “Not a word was spoken, not a word read, not a prayer offered,” the concerned man lamented. And yet, in his mind, “‘Little Joe’ never did anyone harm . . . so far as is known her life was pure, although disguised as a man. . . . And who can say they never sinned more than ‘Little Joe,’ and who knows the cause that made her do as she did? A cause that might have made [any] one of us a vagabond, a drunkard or a criminal. So let us pray that ‘Little Joe’s’ soul has been received at the ‘Pearly Gates’ as we would wish our’s to be received.”

As this Rockville correspondent’s words evince, despite the fact that Joe Monahan had resided for many years in this remote corner of the Idaho-Oregon borderlands, few there knew a great deal about him. What seems certain about this Idaho pioneer, in fact, composes a rather short list. Monahan shows up in southwestern Idaho as early as the 1870 federal census. He was born about 1850; the census over the years varies somewhat on the exact year. Most sources identify his birthplace as New York . . . Monahan voted in the Republican primary on 28 August 1880 some sixteen years before women in Idaho received suffrage rights. When he died, his estate included about one hundred head of cattle. . . .

Over the days following the deathbed mystery of Monahan, locals in the Idaho-Oregon border country began to relate to the press additional bits of information that they claimed to have learned over the years about their secretive neighbor whose national celebrity was now growing. These stories pretty much held to 1867 as the year that Monahan originally showed up in Silver City. They explain that he began working there first in a livery, followed by a stint in a sawmill. He struck it big in mining, accumulating upward of $3,000, but he had the misjudgment of entrusting the sum to a shady mining superintendent to invest in the business’s stock. Instead, the rascal departed the country, absconding with Monahan’s life savings. Doggedly starting anew, Monahan began selling milk from a cow and eggs from a few chickens he still retained and worked odd jobs here and there until he had accumulated somewhere between $800 and $1,000. He held on to his money this time, taking it with him when he left Silver City and moved across the divide to Succor Creek in about 1883. There he built a rather mean cabin, which some described as little more than a chicken coop while others likened the shack to a dugout. He fenced in forty acres and hired, at least for a short time, a Chinese laborer to help cut grass to feed the one cow and one horse he had brought with him to his new homestead. Over the years Monahan saw his stock increase, tending it about as carefully as he did his earnings. He became known as something of a miser, living sparingly in his cabin, dressing poorly, and often denying himself food, though availing himself of the hospitality that neighbors gladly and often provided. During these years, Monahan also took his civil duties seriously, reportedly voting in every election and serving several times on a jury. Locals also recalled that he could well handle a revolver and a Winchester rifle and that he had become an accomplished horseman.

As the news related these bits and pieces of Monahan’s life, papers farther afield described the revelation of his successful masquerade as causing a local sensation. An Olympia, Washington, publication, for example, explained with the certainty of an eyewitness that “when friendly neighbors were preparing the body for burial, the community was given a decided shock when it was announced that ‘Joe’ Monahan was a woman.” In reality, that Monahan turned out to be physically female caught hardly anyone in and about the Owyhees off-guard. . . . [Friend] William Schnabel . . . explained rather sensitively that “it was always surmised that Joe was a woman. . . . He was a small, beardless, little man with the hands, feet, stature and voice of a woman.”

The 1880 census lends credence to Schnabel’s story. That year, a local farmer and father of six by the name of Ezra Mills served as the census enumerator for District 29 Owyhee County, Idaho Territory, the very census tract in which both he and Monahan resided. . . . For Monahan’s sex, Mills recorded “M” (male) in the appropriate column but took the time to pencil in next to it the editorial comment “Doubtful Sex.” Clearly, for years locals had suspected that Monahan was a woman. But, as Schnabel explained, “no one could vouch for the truth of it. . . . He never would reveal his identity and all cowboys respected him. . . . He never told a word to his best friends who he was and what he was.”

. . . [R]esidents of the Owyhees, although they might have wondered for years and maybe even “surmised” that Joe was a woman, nevertheless had long accepted Monahan as a man, one who was deeply enmeshed in their community. Moreover, the cowboys of the area, to use Schnabel’s words, “treated him with the greatest respect, and he was always welcome to eat and sleep at their camp.”