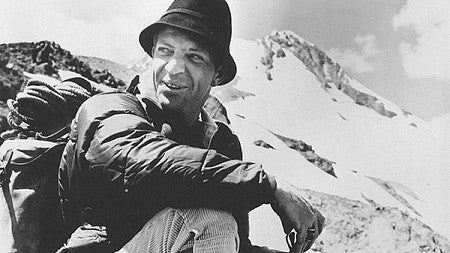

A Minnesota native, Jerstad, who went by Lute, moved to the Pacific Northwest with his family when he was 13 years old. An excellent athlete who played basketball at Pacific Lutheran University, he honed his mountaineering skills on Mount Rainier in Washington, summiting the 14,400-foot peak more than 40 times in his life. It was there that he and the main contingent of the American expedition trained, testing their skills, endurance, teamwork, and equipment. The group left for Nepal confident and well prepared.

The trip from Katmandu to the mountain's flank—a gain of roughly two-and-a-half miles in altitude—is not an easy one. On February 20, 1963, the climbers, accompanied by 37 expert Sherpa guides and 908 porters carrying 53,000 pounds of food, oxygen, fuel, and equipment, began a journey of more than 100 miles. After four weeks of trekking, the expedition reached Base Camp, which, at 17,800 feet, was some 3,400 feet higher than Rainier's summit. (For perspective, if you add the elevation of Mount Hood to that of Base Camp, you get 29,050 feet—almost exactly the height of Everest.)

The expedition members would spend the next six weeks getting acclimated to the high altitude. Most people begin to feel the effects of oxygen deprivation at 8,000 feet, and few are able to function without supplemental oxygen above 18,000 feet. The Americans trained, made various climbs, and scouted the area. A sobering reminder of the stakes of their undertaking occurred on March 23, when one of the party, Jake Breitenbach, was crushed in an icefall, his body lost forever, entombed amid Everest's vast crags and crevices.

On April 30, Jerstad and a group of three climbers reached Camp 5 and the South Col, the penultimate stop before the summit. Meanwhile, American Jim Whittaker was higher up the mountain at Camp 6, poised to attempt a final ascent. The next day he succeeded, becoming the first American to top Everest. He and Sherpa Nawang Gombu stood in powerful wind amid temperatures dropping to –30, surveying Earth from its highest point. They took photos and planted an American flag before running out of oxygen and being forced to cut their hard-won celebration short.

When the 34-year-old Whittaker and Gombu descended to Camp 5, their appearance startled Jerstad, who wrote, "The physical nightmare they had been through was written on their faces. Jim resembled an old man, 30 years older. His face was heavily lined, his eyes were bloodshot, and his skin was blue. I've never seen a man age so much in so few hours in my life."

With the good news that Whittaker had summited Everest came the bad: There was no oxygen for Jerstad and his group to finish the final legs of the ascent.

They returned to Base Camp, restocked their supplies, and weighed various plans for what to do next. Some of the men wanted to attempt a passage up the virgin western ridge, and others, including Jerstad, wanted simply to stand at the top. In the end, they agreed that four climbers would take one last shot. Jerstad and National Geographic photographer Barry Bishop would head up the South Col, while Tom Hornbein and Willi Unsoeld would try to become the first men to summit Everest from the west. After three weeks of slowly progressing toward Camp 6, Jerstad and Bishop awoke on the morning of May 22, exhausted and broken down physically, but ready to make the attempt.

Their pace was nearly a crawl, one laborious step, then two or three or four swallows of oxygen, followed by another step and more oxygen. It took two hours to move 200 feet. Finally, at 3:15 p.m., Jerstad and Bishop together became the second and third Americans to reach the summit of Mount Everest. Whittaker's American flag flapped in the wind, tattered after just a few weeks of exposure to the extreme environment.

Jerstad scanned the western ridge but found no sign of Unsoeld and Hornbein. Something was wrong. Running out of oxygen and pushed to their physical limits, Jerstad and Bishop did what they had to do and started their descent.

Unsoeld and Hornbein reached the summit from the west—but nearly three hours after they were scheduled to arrive. With night approaching, the two dared not savor their hard-won accomplishment for long. They pushed down the steep slope in the tracks left by Jerstad and Bishop, eventually catching up to them.

At 12:30 a.m., the exhausted foursome made a bivouac—an unsheltered camp—on an outcropping at 28,200 feet. It was the highest anyone had ever camped. With little protection in the relentless winds, the men should have died. None had oxygen. All suffered from frostbite. But for the first time during the trek, the wind stopped. The temperature rose, and survival became something more than an oxygen-deprived hallucination. The four men huddled under the stars more than five miles above sea level and waited out the night. Jerstad later described their survival as a miracle.

* * *

The rest of the Everest tale is like the gradual recovery after a fever breaks. Slowly, painfully, they made their way back home, with Bishop and Unsoeld's toes ravaged by frostbite. Jerstad's feet suffered as well, and he was carried down the mountain on a stretcher. Eventually, he recovered.

Afterwards, Jerstad refocused his estimable energies on other pursuits; conquering Earth's mightiest peak was a steppingstone to other accomplishments in his life.

"Everest doesn't interest me any more," he told John D. McCallum, author of Everest Diary, a 1966 account of Jerstad's adventure. "I've already been there. It's done. But there are other mountains and other challenges—I'll be there."

One of those challenges was academic; Jerstad earned his doctorate at the University of Oregon just a few years after returning from Everest. (While on campus he taught drama and acted the role of R. P. McMurphy in a production of One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest.) After working as a professor at Lewis and Clark College for three years, he launched a guide service in Portland, Lute Jerstad Adventures, offering treks and rafting expeditions. He also ran a mountaineering school, instructing students on Mount Hood and Mount Rainier.

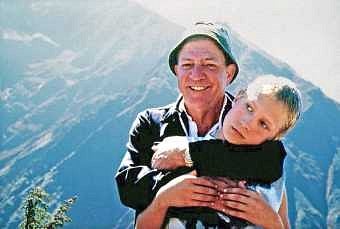

Jerstad's final adventure took place while introducing his 11-year-old grandson, Marshall, to trekking in the Himalayas (see below). Their goal was Kala Patthar, a popular and relatively easy to reach prominence that offers a stunning panorama, including Everest and the path Jerstad had followed decades earlier to its top. Just 500 feet from this vantage point, Jerstad suffered a heart attack and died at age 61. His ashes were buried at a monastery not far from Everest.

Peak Experience, and After

Marshall Cook was 11 years old in the fall of 1998 when his grandfather took him to Asia; first to Thailand and then to Kathmandu, Nepal. For a kid from Portland, it was serious culture shock.

"There were cows walking around in the city streets and people with elephantiasis," says Cook, now 27. "But my grandfather did a really great job of explaining it all to me. Being there was second nature to him."

Lute Jerstad was no ordinary grandpa.

From Kathmandu, they flew to Lukla (9,300 feet) and began a fateful trek near towering Mount Everest, where 35 years earlier Jerstad had stood atop the world's highest peak. On their way, they visited famous sites such as the Namche Bazaar and Tengboche Monastery. "The whole time, he's teaching me about the culture," Cook says.

Two days later, Jerstad and a group of family members and friends hiked toward Kala Patthar, a prime spot for viewing Everest. Just short of their destination, Jerstad suffered a fatal heart attack.

Local guides accompanying the hikers placed the body in a tent atop a hill. Brightly colored prayer flags surrounded the tent and fluttered in the gusting Himalayan wind.

The events of that day changed Cook "in every way possible," he says. Facing death at such a young age and so close at hand, he felt shock, sadness, and grief. But as the years passed and the boy moved into adulthood (becoming a middle school science teacher in Forest Grove and a wrestling coach at Pacific University), he's grown more thoughtful about and inspired by his grandfather.

"He died doing exactly what he wanted to do," Cook says. "He accomplished just about every dream. He checked off everything on his bucket list."

One Step at a Time—Another UO Grad Makes the Everest Grade

Near the top of Mount Everest, mountaineers enter the "death zone," where only the hardiest of humans can survive without supplemental oxygen. John Dahlem '65 and his son Ryan entered the zone together. Even though they had oxygen, John was nearly exhausted. He'd climbed the steep Lohtse Face the day before, plodding up steps hacked into the thick ice, the pinnacle of Everest looming a few thousand feet away. He didn't think he could make it past the notoriously challenging Hillary Step and then on up to the summit.

He told Ryan to go on without him and represent the family.

But then came a role reversal, with son taking care of dad. "It really was classic," the elder Dahlem recalls with a laugh. "Ryan says, 'Why don't we just go another five minutes?' I used to say the same thing when he was a kid. So we continued for many 'another five minutes.'"

Dahlem was nearly 67 at the time (the spring of 2010); Ryan, 40. Step by step, in five-minute increments, they became the oldest father-son duo to have summited Everest.

With that climb, the two nearly completed the so-called "grand slam" of mountaineering, summiting the highest peak on each continent (leaving only a relatively minor Australian peak yet to climb). But, Dahlem says, the biggest reward from the experience was spending time with his son.

A former high school teacher, principal, and wrestling coach in Southern California, Dahlem got an unexpected benefit from his trekking accomplishments. After he gave then Ducks football coach Chip Kelly the UO pennant he'd taken to the top of Everest, Kelly invited Dahlem to speak to the team about the adventure. Dehlem's inspiring words touched on discipline and taking it one step at a time. In other words, give five minutes, and then five more, till you reach your goal.

—By Matt Tiffany

Matt Tiffany, MS '07, is a freelance writer and editor based in Portland. He's a frequent contributor to Oregon Quarterly and an infrequent climber of mountains, although he hopes to rectify the latter.