On Christmas Day in 1931, a seven-ton circus elephant smashed his way out of the Portland, Oregon, barn where he was being kept. The enraged animal, still partially shackled but now free of the building, turned and attacked it, broken chains swinging from his tusks. The National Guard and police were called, and responded with rifles raised, prepared to kill the elephant if he broke free of his remaining bindings and charged the crowd of onlookers that soon numbered in the thousands. But the animal's handlers eventually were able to ensnare one of the elephant's legs with a steel cable, toppling him and bringing the crisis to an end.

It was but one tumultuous chapter in the sad life of Tusko, Oregon's most famous elephant.

Edward Davis keeps a file of faded newspaper clippings from the 1920s and '30s, heartbreaking accounts detailing Tusko's misfortunes at the hand of man. An assistant professor in geological sciences in the College of Arts and Sciences, Davis is also paleontological collection manager for the University of Oregon Museum of Natural and Cultural History.

Tusko's bones were donated to the university in 1954, and Davis oversees their use today for education, research, and outreach. On this autumn afternoon, he leads a visitor to a nondescript campus building and with a turn of a key, unlocks a remote, underground room. The elephant's 200 bones, for years scattered throughout various storage rooms across campus, have recently been brought together here, where they sit neatly on shelves covering two walls. In their disassembled state, the bones only hint at the massive size of the whole animal. The ribs are like baseball bats; a single spinal vertebra has the shape and span of a dinner plate. The skull alone weighs roughly 200 pounds.

Davis studies fossils for a living, so he knows well the ability of animal bones to tell a story. As he runs a hand over a four-foot-long femur, feeling the fibrous imperfections in the rock-hard matter, the story of Tusko the elephant begins to emerge once again: his troubling life, his service to the university in death. Even a possible future . . .

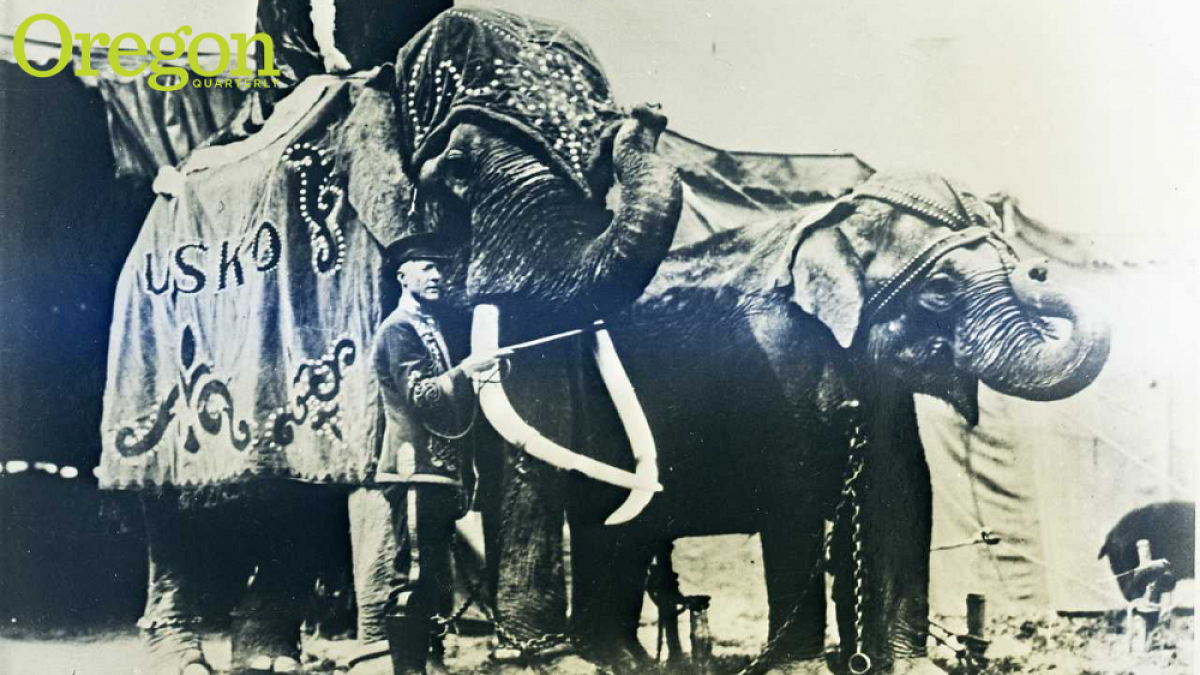

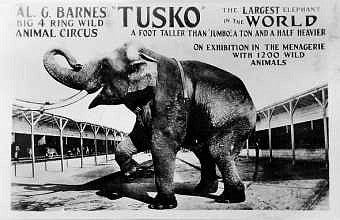

In his day, Tusko was likely the largest elephant, by weight, in captivity. The famous Jumbo was taller, but for sheer mass, Tusko was unrivalled, weighing in at more than seven tons. Plucked from Thailand at six years old—still a child in elephant terms—his destiny was the circus. By adulthood he sported seven-foot tusks and was billed as the "Mighty Tusko, Biggest Beast That Walks the Earth," appearing at events across North America in the 1920s.

As with most circus elephants of the time, Tusko's treatment was questionable, at best. Trainers used brute force to try to tame these gigantic wild animals, beating them with bullhooks, long-handled devices with a sharp steel hook and poker on one end. The method met with only limited success. Circus elephants sometimes killed their handlers and even bystanders who came too close; the unfortunate animals were typically destroyed as a result.

Tusko, as a male or bull, presented a special concern because he periodically experienced "musth," a condition accompanied by a surge in reproductive hormones and highly violent behavior. For years, he was kept in a "crush" cage for three or four months at a time during musth, unable to move, let alone lie down.

Described once as "the world's most chain-bound elephant," Tusko tried a number of times to escape. In 1922, he broke free of his tent in Sedro-Woolley, Washington, overturned several wagons, and reportedly came across a supply of "bootlegger's mash," which he consumed.

The barn-smashing incident in Portland is well documented by Tusko's longtime handler, George "Slim" Lewis, in I Loved Rogues, a book he authored in 1955 with a Seattle journalist. Lewis embodied his era's dichotomous treatment of circus elephants: He kept Tusko in chains so tight they became embedded in the animal's flesh and yet he clearly loved the elephant, devoting his life to Tusko, feeding and bathing him and repeatedly fending off attempts by others to have the animal destroyed.

Lewis became Tusko's caretaker after a promoter abandoned the elephant in Salem. As the penniless pair made their way north, scraping by on viewings of Tusko offered for 10 cents apiece, their misadventures were regularly covered by the papers. The Denver Post in 1932 ran a full-page feature on Tusko, recounting with great delight the earlier reports involving moonshine and portraying the elephant's decline as the result of addiction: "What the Rum Demon Did to This Ten-Ton Circus Star," the headline blared. "Once the Pride of a Big-Top Circus and Now Just a Ten Cent Exhibit in an Old Boiler Factory."

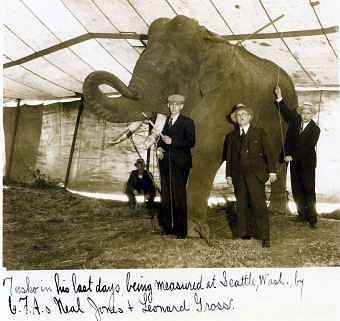

For Lewis and Tusko, the story ended in Seattle. With winter approaching and the pair camped in an unheated tent, city officials granted the elephant asylum, of sorts, in the Woodland Park Zoo in the fall of 1932. Sixty-five thousand people turned out to see Tusko on a following Sunday; Mayor John Dore was among the elephant's admirers. Lewis described those days as some of the happiest of Tusko's life.

The elephant died less than a year later, of a blood clot in his heart. With Tusko on his deathbed, trembling violently, Lewis removed the animal's chains and allowed the elephant to pull him close with his trunk. "I made up my mind that . . . he would die free, with no manmade chains on him, free as he should always have been," Lewis wrote. "At 9:30 that morning Tusko left me. May we meet again someday, where the grass is tall and green, and there are no chains."

* * *

Eighty years later, Tusko is helping students on the University of Oregon campus to distinguish mammoths from mastodons.

The university's acquisition of Tusko is the stuff of legend. As the story goes, ownership of the elephant's remains eventually transferred to a UO alum who was less than enthusiastic about his prized possession remaining in Seattle. "No way my elephant is staying up there with all those Huskies," the Duck reportedly said. While that part of the story remains unconfirmed, we do know that a Mr. D. M. Bull of Eugene donated the skeleton to the university on December 21, 1954.

Samantha Hopkins, assistant professor of geology in the Robert D. Clark Honors College, has for years used Tusko's bones in the courses she teaches on vertebrate paleontology, evolution, and animal pathology. It's a rarity for a natural history museum the size of the UO's to have a nearly complete elephant skeleton at its disposal, she says.

The 50-million-year-old vertebrate fossil record in Oregon is strewn with the fossilized remains of the elephant's relatives, including the mammoth and mastodon. By comparing fossil finds with Tusko's skeleton, students learn to discern which are which (a mammoth's bones are more like the elephant's). "Anytime you can show students what you're talking about in addition to saying it, it's going to stick with them a lot more," says Hopkins. "You can take a dinosaur leg bone and say, 'Let's think about how big it is, relative to the bone of Tusko.' Paleontology is a tactile science; a picture on your iPhone is not going to give you a sense of how big an elephant is."

Hopkins illustrates the influence of evolution by comparing Tusko's skeleton with those of dogs and cats. All three have the same types of leg bones, for example, but there is a bend in the elbows and knees of dogs and cats, while the legs of elephants evolved with a straight, columnar orientation—the better to support the massive weight riding on them.

As mammals, elephants are "outliers," Hopkins says, with prodigious size and unusual features that force students to rethink their assumptions about vertebrate animals. "Their reaction is, 'Man, that's just weird—those things are freaks,'" Hopkins says. "I don't think I've ever had a student who hasn't found the experience of being with an actual elephant skeleton something that readjusted their opinion on things. I always take students to see Tusko because I know it's going to readjust their point of view."

Tusko's skeleton, Hopkins says, tells a story. That's something that can't be duplicated by the pristine-but-generic artificial animal skeletons that are produced as teaching tools. Porous and pitted overgrowths around the elephant's joints are a telltale sign of arthritis, and the fibrous texture of some bones indicates the strain placed on them to support Tusko's mass as he grew. The animal's skull is of particular interest to Hopkins's students. They're fascinated by the 18-inch-square section of bone cut out during a necropsy (an animal autopsy)—what's going on there?—and their examination inevitably leads to difficult discussions about the animal's life. Small cavities in the elephant's skull, for example, evidence a calcium deficiency, as Tusko's system compensated for years of malnutrition by taking the element from other parts of his body.

Vertebrate paleontology tends to draw students with strong stomachs—they're excited by the thought of dissecting an animal corpse to learn its pathology. But Hopkins has found that providing too much information about Tusko's mistreatment makes some students uncomfortable. She feels out her classes out each year to determine where the line is. It's important to Hopkins that students consider Tusko just as she wants them to view million-year-old fossils—as living, breathing creatures that once walked the Earth.

"Tusko is not a perfect, clean skeleton—you can see his history written on the bones," she says. "That was an individual animal. Some people are probably uncomfortable with who these animals were, but I like the students to think about the dead animals as dead animals. They represent individuals."

* * *

The elephant's bones are all together at last, accounted for and housed "in a secure, undisclosed location," Davis says. He doesn't want to reveal the spot, fearing thieves or others who might disturb the skeleton. But Davis will not call this Tusko's final resting place.

He hopes to see the elephant restored one day. The bones could be reconnected, he says, and displayed in a prominent spot on campus, where they could be of better service to the university community and the public. The money for such a project is one concern; Davis is also hard-pressed to identify a space on campus large enough to accommodate the frame of a seven-ton animal that stood 10 feet tall.

Still, he's optimistic. Tusko, in death, has contributed much to the university in the teaching of paleontology, evolution, and animal pathology; there could be an even more stirring lesson—and fitting tribute—in a deeper exploration of his life. "He's a great example as far as the history of how we treated animals," Davis says. "If he can serve as a reminder to us today that we need to be more humane, that alone is reason enough to have him put back together.

—By Matt Cooper, University Communications